Dan Falvey fishes aboard the 50-foot FV Magia out of Sitka, Alaska, for Pacific cod, black cod, and halibut. Alongside that boat two cameras lean out over the water, each pointed at the spot where the longline emerges from the deep. When the hydraulic winch kicks into gear and the line starts coming in, the cameras switch on, recording high-definition video of everything the fishermen pull out of the water.

Knowing what species come out of the water, and how much of each, is key to managing fisheries sustainably. In many fisheries, boats are required to carry an observer onboard to record that data.

But on FV Magia, “There just isn’t enough bunk space to take an observer out,” Falvey says. He hopes the cameras—part of an experimental electronic monitoring system—will make carrying a human observer unnecessary.

In addition to being a fisherman, Falvey is the project coordinator for the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association. He coordinates the efforts of 24 fishermen who are working with scientists to develop an electronic monitoring system for small vessels in the Alaskan halibut IFQ fishery.

Similar systems are being developed in five other U.S. fisheries—three on the West Coast and two in New England and the Mid-Atlantic. They all share a common goal: to collect the data that scientists need without getting in the way of the fishing. But each fishery is different—different species, different gears, different boats—and there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Some Systems are More Complicated than Others

Four fleets, all in Alaska, have fully implemented electronic monitoring to date. These fleets fish for groundfish, including walleye pollock, the biggest—and one of the most valuable—catches in the nation. The boats are large and fully modernized, making it relatively easy to integrate new electronics and find space for cameras and other hardware.

In addition, these electronic monitoring systems are relatively simple, akin to the security camera systems you see at the mall. They record workers to ensure proper handling of catch and bycatch, but the data collection—identifying the species and tallying the catch—is still done by human observers.

But many of the systems still in development, including the one on FV Magia, are much more complicated. In these systems, the video will be used not only to monitor for compliance but also to identify which species are being brought on board and how much of each. Initially at least, that data will be tallied by onshore video reviewers.

This is more difficult than it sounds. Wet or fogged lenses can render video unreadable, as can glare and low light. And while some species are relatively easy to identify, others, like various species of rockfish, are difficult to tell apart in person, let alone on a computer screen.

The security camera–based systems like those on the larger pollock boats—compliance monitoring systems—are relatively simple. But systems designed to tally catch data—catch accounting systems—“are much more complex,” says Chris Rilling of NOAA Fisheries, who leads the agency’s North Pacific Groundfish and Halibut Observer Program. “The technical hurdles are much greater.”[xyz-ihs snippet=”adsense-body-ad”]

Shared Lessons and Shared Resources

“There’s still a lot of work to do before we can deploy these on a commercial scale,” Falvey says of the catch accounting system he’s working on. In addition to problems with fogged lenses and low light, the costs of reviewing and archiving tremendous volumes of video data can eat into any potential cost savings.

“But we shouldn’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” Falvey says, so fishermen and scientists are drawing on lessons learned in other fisheries to solve these problems. For instance, the cameras being developed for halibut boats will be deployed in other fisheries. The software that onshore reviewers use to scan video is also shared across fisheries. And data from Alaska and West Coast fisheries are being stored at a single facility run by the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission.

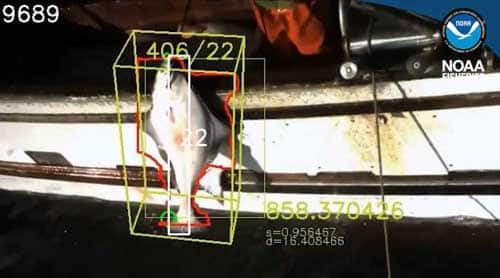

In addition, scientists at the NOAA Fisheries Alaska Fisheries Science Center are developing new technologies that will solve common problems across many fisheries. These include 3D cameras and computer vision—a type of image recognition based on artificial intelligence—to automatically identify fish species and generate the weight estimates needed to set sustainable catch and bycatch limits. These systems, however, are still a few years away.

George Lapointe, NOAA’s national coordinator for electronic monitoring technologies, says that although different fisheries require different solutions, there are many lessons that can be shared. “What percentage of a fleet should carry electronic monitoring systems? How do we review the video? How long do we hold the data?” asked Lapointe. “These are all common themes that drive system costs.”

In some fisheries, the costs of electronic monitoring will outweigh any savings. In others, electronic monitoring will be the way to go. As we learn how to build better systems, and as new technology comes online, more fisheries will fall into the second category.

In the meantime, scientists and fishermen continue to work together, with regional fishery management councils helping to coordinate their efforts. “We can’t just impose a system on fishermen,” said Rilling. “We need to work with fishermen in each separate fishery to determine what works best on their boats.”

That type of collaborative effort, repeated in each fishery, takes time. But it’s the only way to develop cost-effective electronic monitoring systems that produce the data that scientists need while allowing fishermen to do their jobs.

Source: NOAA Fisheries [xyz-ihs snippet=”Adversal-468×60″]