A team led by the University of Colorado Boulder looking for clues about why Earth did not warm as much as scientists expected between 2000 and 2010 now thinks the culprits are hiding in plain sight — dozens of volcanoes spewing sulfur dioxide.

The study results essentially exonerate Asia, including India and China, two countries that are estimated to have increased their industrial sulfur dioxide emissions by about 60 percent from 2000 to 2010 through coal burning, said lead study author Ryan Neely, who led the research as part of his CU-Boulder doctoral thesis. Small amounts of sulfur dioxide emissions from Earth’s surface eventually rise 12 to 20 miles into the stratospheric aerosol layer of the atmosphere, where chemical reactions create sulfuric acid and water particles that reflect sunlight back to space, cooling the planet.

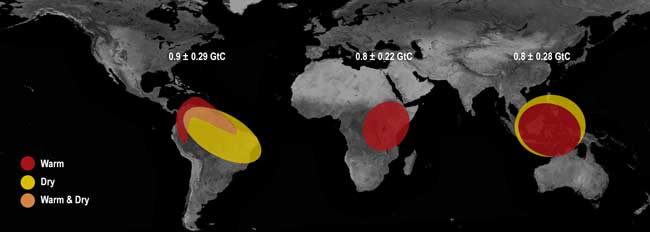

|

|

Neely said previous observations suggest that increases in stratospheric aerosols since 2000 have counterbalanced as much as 25 percent of the warming scientists blame on human greenhouse gas emissions. “This new study indicates it is emissions from small to moderate volcanoes that have been slowing the warming of the planet,” said Neely, a researcher at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, a joint venture of CU-Boulder and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

A paper on the subject was published online in Geophysical Research Letters, a publication of the American Geophysical Union. Co-authors include Professors Brian Toon and Jeffrey Thayer from CU-Boulder; Susan Solomon, a former NOAA scientist now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Jean Paul Vernier from NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va.; Catherine Alvarez, Karen Rosenlof and John Daniel from NOAA; and Jason English, Michael Mills and Charles Bardeen from the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder.

The new project was undertaken in part to resolve conflicting results of two recent studies on the origins of the sulfur dioxide in the stratosphere, including a 2009 study led by the late David Hoffman of NOAA indicating aerosol increases in the stratosphere may have come from rising emissions of sulfur dioxide from India and China. In contrast, a 2011 study led by Vernier — who also provided essential observation data for the new GRL study — showed moderate volcanic eruptions play a role in increasing particulates in the stratosphere, Neely said.

The new GRL study also builds on a 2011 study led by Solomon showing stratospheric aerosols offset about a quarter of the greenhouse effect warming on Earth during the past decade, said Neely, also a postdoctoral fellow in NCAR’s Advanced Study Program.

The new study relies on long-term measurements of changes in the stratospheric aerosol layer’s “optical depth,” which is a measure of transparency, said Neely. Since 2000, the optical depth in the stratospheric aerosol layer has increased by about 4 to 7 percent, meaning it is slightly more opaque now than in previous years.

“The biggest implication here is that scientists need to pay more attention to small and moderate volcanic eruptions when trying to understand changes in Earth’s climate,” said Toon of CU-Boulder’s Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. “But overall these eruptions are not going to counter the greenhouse effect. Emissions of volcanic gases go up and down, helping to cool or heat the planet, while greenhouse gas emissions from human activity just continue to go up.”

The key to the new results was the combined use of two sophisticated computer models, including the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model, or WACCM, Version 3, developed by NCAR and which is widely used around the world by scientists to study the atmosphere. The team coupled WACCM with a second model, the Community Aerosol and Radiation Model for Atmosphere, or CARMA, which allows researchers to calculate properties of specific aerosols and which has been under development by a team led by Toon for the past several decades.

Neely said the team used the Janus supercomputer on campus to conduct seven computer “runs,” each simulating 10 years of atmospheric activity tied to both coal-burning activities in Asia and to emissions by volcanoes around the world. Each run took about a week of computer time using 192 processors, allowing the team to separate coal-burning pollution in Asia from aerosol contributions from moderate, global volcanic eruptions. The project would have taken a single computer processor roughly 25 years to complete, said Neely.

The scientists said 10-year climate data sets like the one gathered for the new study are not long enough to determine climate change trends. “This paper addresses a question of immediate relevance to our understanding of the human impact on climate,” said Neely. “It should interest those examining the sources of decadal climate variability, the global impact of local pollution and the role of volcanoes.”

While small and moderate volcanoes mask some of the human-caused warming of the planet, larger volcanoes can have a much bigger effect, said Toon. When Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines erupted in 1991, it emitted millions of tons of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere that cooled the Earth slightly for the next several years.

The research for the new study was funded in part through a NOAA/ ESRL-CIRES Graduate Fellowship to Neely. The National Science Foundation and NASA also provided funding for the research project. The Janus supercomputer is supported by NSF and CU-Boulder and is a joint effort of CU-Boulder, CU Denver and NCAR.