Second reported sighting in eastern North Pacific waters south of the Aleutian Island chain.

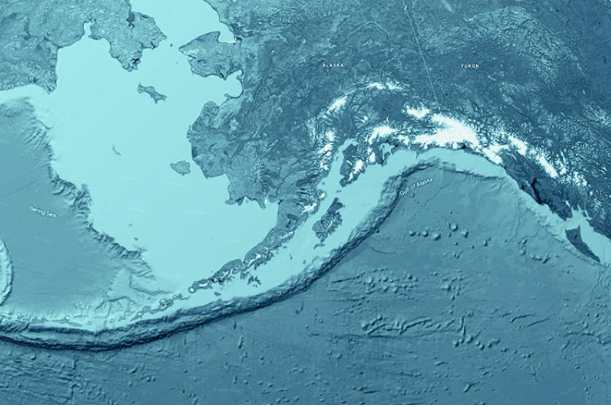

A new scientific paper discusses the first NOAA Fisheries record of a bowhead whale in Southeast Alaska. It is only the second documented sighting of this Arctic species in the eastern North Pacific, south of the Aleutian Islands. The whale was observed by a team of scientists working in Sitka Sound in March 2024.

“This sighting is important because it is a first for a pretty big region,” said Ellen Chenoweth, lead author on the study from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. “This is the first documented sighting of a bowhead whale in Southeast Alaska. It’s not the furthest south they have been seen, but it’s very notable because of how far it is from its typical range. It raises a lot of questions about what was going on with this animal that we can’t answer.”

>

Rare Sighting on a Survey

The crew were using a 25-foot motorboat in Sitka Sound to photograph and identify humpback whales that had been observed bubble-net feeding in the area. Humpback whales are often present in large numbers in Sitka Sound in March, feeding on pre-spawn herring.

They also spotted gray whales, likely feeding on herring eggs near shore. After identifying several humpback whales in smaller groups, the crew was heading back to Sitka when they spotted another whale.

The vessel slowed to photograph this whale, but it didn’t appear to be a humpback. The whale was small, visible only by its head and jaw, which had a distinct arch. The crew took two photos before the whale submerged.

The crew stayed on site, scanning for its resurfacing, and lowered a hydrophone to listen for vocalizations, but didn’t hear any. Gray whales were nearby, but did not appear to be associated with the whale in question.

The whale, identified by experts through photographs, exhibited unusual behavior. It was only observed with its head and jaw visible as it surfaced to breathe. Over the next month, additional sightings of the whale were reported. No feeding or social behaviors were noted, and on only one occasion was the back—which lacked a dorsal fin—visible.

How to Spot a Bowhead Whale

“Outreach is important so that people know what to look for, like the bowhead’s unusual head and lack of dorsal fin,” said Kim Shelden, marine biologist at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s Marine Mammal Laboratory. “To identify a bowhead whale, look for distinctive features such as: no dorsal fin; a narrow, arched upper jaw; paddle-shaped pectoral flippers; a black body; white chin patches; and some white coloring on the peduncle (the muscular area where the tail connects to the body),” said Shelden. Bowhead whales are similar in size and appearance to North Pacific right whales, but do not have callosities (raised patches of hardened skin on the head and along the jawline). These patterns are often used to identify individual right whales.

Bowhead whales are a long-lived species that typically inhabits Arctic and subarctic waters. These baleen whales have evolved to survive in ice-covered waters. Bowheads have a thick blubber layer and blowhole atop a pinnacle of blubber that enables them to break through heavy ice to form breathing holes.

Four populations are currently recognized as stocks for management purposes, based on migratory patterns. Two of these stocks occur in the North Pacific: the Western Arctic (also known as the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort) and the Sea of Okhotsk.

The Sea of Okhotsk stock is thought to reside year-round within this sea. The Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort stock migrates annually from wintering areas in the Bering Sea, through the Chukchi Sea, to summer feeding areas in the Beaufort Sea.

Other Reports of Bowhead Sightings South of the Arctic

The fossil record indicates that pre-historically species within the genus Balaena, of which bowhead whales are the only living species, occurred as far south as 35 ° N. During the last glacial maximum around 3 million years ago, they relied more on the expanding northern ice-covered habitats. This led to an increase in their population.

With recent changes in the Arctic due to sea ice melt associated with rising global temperatures, some subarctic species, such as killer whales are moving north. Killer whales are known whale predators. Humpback and fin whales, potential competitors with Arctic whales for prey resources, are also moving north.

In the last few decades, some bowheads have been seen outside their usual range. In August 2010, two bowhead whales—one from West Greenland and the other from Alaska—entered the Northwest Passage from opposite directions. Both were tagged with satellite-linked transmitters. Scientists documented that the whales stayed in the same area for 10 days. This was the first time where scientists observed the two whale stocks’ spatial and temporal overlap.

“We know of only two previous observations of bowhead whales in the North Pacific,” said Kim Shelden. “In 1969, a subadult male bowhead whale was captured and died in Osaka Bay, Japan. In 2016, a young bowhead whale was photographed skim feeding near British Columbia, Canada. This specific bowhead whale sighting in March 2024 may be an indicator of rapid changes occurring in the Arctic,” said Shelden. She also noted recent sightings of other Arctic species in U.S. West Coast waters, such as beluga whales and a ribbon seal.

Collaboration for Identification

After local media reported on the sightings, members of the public reported several more sightings. Without this outreach, the detailed video evidence shared here likely wouldn’t have reached scientists. Indigenous Knowledge holders in Sitka and Utqiagvik provided valuable insights. They helped to identify and understand the sighting, highlighting the importance of Indigenous Knowledge in Alaskan communities.

Without further research, including genetic testing and additional sightings, the origins and health condition of this specific whale will remain unknown. This sighting underscores how changes in the Arctic ecosystem, like sea ice loss, may lead to more occurrences of Arctic species in southern regions. Both scientific and Indigenous knowledge are important to document and understand these events.

The loss of sea ice in polar regions will impact many species that depend on ice for survival like bowhead whales. Having information about their movements is critical for complying with federal law under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act, co-management agreements, and enabling responsible ocean development.

NOAA