When U.S. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen announced a new policy recently to keep asylum-seekers in Mexico while they wait for their cases to be adjudicated, it was the latest in a string of Trump administration policies affecting asylum this past year.

According to requirements laid out by the U.N. Convention on Refugees in 1951 and adopted by the United States, applicants for asylum must meet three requirements: prove they have a “reasonable fear” of persecution in their home country; fear persecution because of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social class; and prove their home country’s government is either involved in the persecution or unable to control it.

In 2018, the Trump administration introduced at least seven policies affecting asylum. Immigrant advocates and immigration hardliners say these policies were attempts to deter immigrants from entering the United States.

New standards for credible fear

When migrants cross the U.S. border either legally or illegally and request asylum, they are first given a credible fear interview with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officers. Asylum-seekers who successfully complete the interview continue on to the immigration courts for the next stage of the process.

At the beginning of 2018, the administration released new and more restrictive guidelines for passing the credible fear interview. According to news reports, a clause in the new interpretation of credible fear was changed to factor in applicants’ “demeanor, candor and responsiveness” in determining their credibility.

Immigration lawyers have told VOA that trauma, difference in culture, not speaking the language, and the journey from Central America to the U.S. often affect people’s behavior. The new guidance says these circumstances should not be seen as “significant factors” in determining credibility, essentially authorizing asylum officers to consider signs of stress as a reason to doubt an applicant’s credibility.

“By raising the bar at this initial stage … the Service (USCIS) is running the risk of screening out those who have bona fide claims but who lack the ability or sophistication to present them to the asylum officer at this early stage,” Catholic Legal Immigration Network, a nonprofit group that provides legal services to immigrants, said on its website.

[content id=”79272″]

‘Zero tolerance’

On April 6, the Trump administration announced its “zero tolerance” policy at the U.S.-Mexico border. The new guideline directed federal prosecutors to criminally charge every adult migrant illegally entering the country, thus mandating that they remain in detention for the duration of their asylum process.

Before “zero tolerance,” when migrants entered the U.S. between ports of entry, they were charged with a misdemeanor — a minor offense.

The policy notoriously led to the separation of children from their parents, since children cannot be held in a jail setting for a considerable length of time.

The public outcry prompted President Donald Trump to sign an executive order in June rescinding the policy.

According to DHS, more than 2,500 children were separated at the border from their parents or adult guardians from May 5 to June 9.

After the repeal of “zero tolerance,” the Trump administration has unsuccessfully sought court permission to hold children in detention with their parents for indefinite periods.

Domestic abuse

In a rare move in June, then Attorney General Jeff Sessions intervened in the asylum case of a Salvadoran woman who had demonstrated a long history of spousal abuse. Sessions reversed an immigration appeals court ruling that granted asylum to A-B, as she was known. Sessions ruled A-B was ineligible because victims of domestic violence may not be included in the members-of-social-classes provision. The ruling also applied to victims of gang violence.

In December, U.S. District Court Judge Emmet Sullivan put a permanent injunction on Sessions’ order, saying it violated U.S. immigration law and had “no legal basis for an effective categorical ban.”

After Sullivan’s ruling, the White House released a statement.

“Today’s ruling is only the latest example of judicial activism that encourages migrants to take dangerous risks; empowers criminal organizations that spread turmoil in our hemisphere; and undermines the laws, borders, Constitution, and sovereignty of the United States,” White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders wrote.

Turned away

Also in June, reports of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers illegally turning away asylum-seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border surfaced. Though immigration authorities called it a “myth” that asylum-seekers have been turned away at ports of entry, 13 migrants sued the government for just that, filing a lawsuit in July 2017.

Speedier trials

In March, Sessions vacated a 2014 ruling by the Justice Department’s Board of Immigration Appeals which eliminated a requirement that asylum-seekers get a full hearing before an immigration judge — which meant immigration judges are allowed to reject asylum petitions without a full hearing, if at the initial review they have signs of a fraudulent case or are unlikely to succeed.

He also ordered case completion quotas for immigration judges. The move came as immigration judges were rapidly hired.

At a welcoming ceremony for 44 newly sworn immigration judges in September, Sessions told them to carry out their duties according to his orders.

“These decisions will provide more clarity for you. They will help you to rule consistently and fairly. And it is more important than ever that you do just that,” he said.

The immigration data tracker TRAC reports that fiscal year 2018 broke records for the number of decisions by immigration judges granting or denying asylum.

Denials grew faster than grants, pushing denial rates up. About 65 percent of asylum requests were denied. TRAC reports that 2018 was the sixth year in a row that denial rates rose. Six years ago, the denial rate was 42 percent.

Though they eventually leveled, denial rates rose again in June after Sessions restricted grounds on which immigration judges could grant asylum.

Illegal entrants

The Trump administration issued an order on Nov. 9 to restrict asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border by requiring anyone who enters the U.S. illegally not be eligible to request asylum.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued. On Nov. 30, U.S. District Judge Jon Tigar refused to allow the administration to enforce a ban.

The president “may not rewrite the immigration laws to impose a condition that Congress has expressly forbidden,” Tigar stated.

His ruling has since been upheld by an appeals court and the U.S. Supreme Court.

‘Metering’

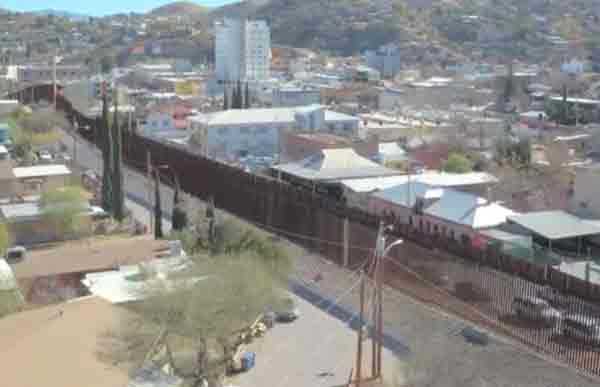

The July case against turning people away at the border was amended in early December to include another practice restricting access to asylum. Called “metering” by immigration advocates and “queuing” by Nielsen, the practice restricts the number of asylum-seekers who can be processed at legal ports of entry at the U.S.-Mexico border, creating a backlog on the Mexican side.

Those hoping to apply for asylum in the U.S. are on a waiting list that is now thousands long. Lawyers say this has created a humanitarian crisis at the border. Some migrants told VOA they had been waiting for weeks.

At a congressional hearing in December, Nielsen defended the practice.

“It’s capacity. It’s capacity,” she insisted.

A CBP spokesperson said from “time to time, we have to manage the queues and address that processing based on that capacity.”

The practice of metering is not new. According to court documents, it happened during former President Barack Obama’s administration.

Partnership with Mexico

At year’s end, the U.S. and Mexico formed a partnership under which asylum-seekers would remain in Mexico while their cases were being processed in the U.S.

Trump administration officials said the Mexican government agreed on its own accord. The changes, whenever they take effect, are expected to affect those who cross illegally and legally. Asylum law experts say this latest policy will end up in court.

Media reports reflect a growing crisis at ports of entry in Mexico where shelters are already overcrowded.

Meanwhile, two children died in border patrol custody after entering the U.S. illegally.

“The system is clearly overwhelmed, and we must work together to address this humanitarian crisis and protect vulnerable populations,” Nielsen said in a statement released Dec. 29 after a trip to El Paso, Texas, one of the nation’s busiest border crossing points.

Aline Barros is an immigration reporter for VOA’s News Center in Washington, D.C.

Source: VOA