Photo by Ned Rozell.

MINTO — Sarah Silas, 89, smiled as she remembered an earthquake that shook her village more than 60 years ago. The floor of her cabin swayed so that her young son staggered away from her.

“My three-year old boy was laughing,” she said inside her log cabin, its front door open to warm air on a golden day. “The ground was moving so much I couldn’t even reach my little son.”

Silas, with her husband Bergman a gracious host to a visiting seismologist, was one of a few people in this village of about 200 who remembered an earthquake in October 1947. The earthquake scientist, Carl Tape, was in Minto to interview elders and check on the installation of a super-sensitive instrument that detects ground motion.

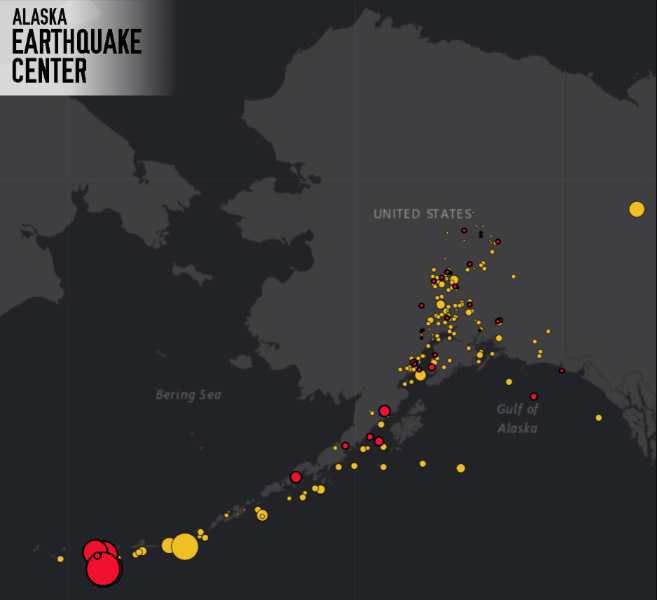

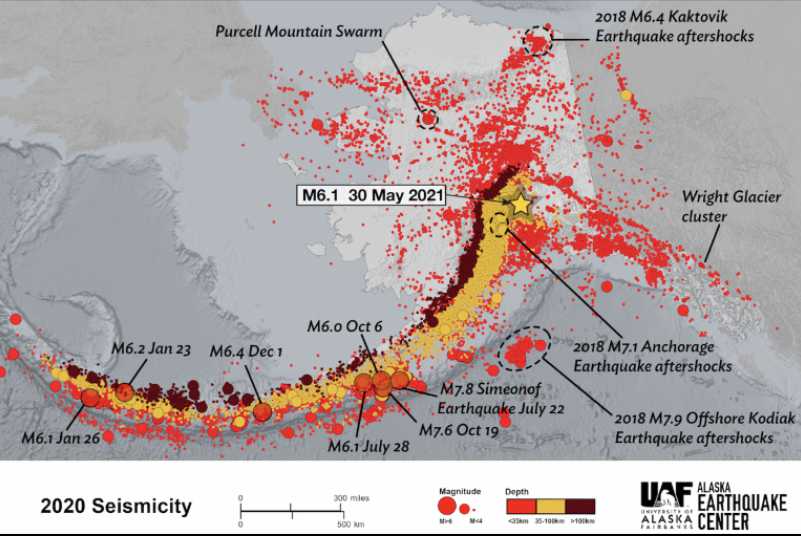

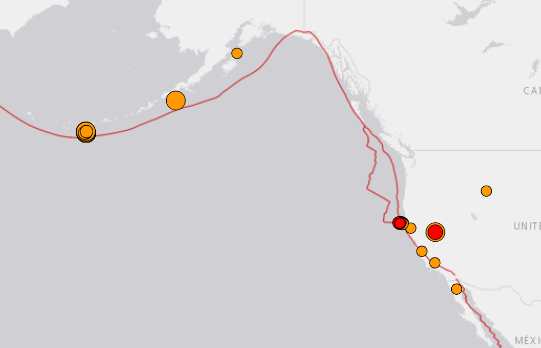

A few blocks away at the Minto airport, two contractors were drilling a nine-foot hole that would soon be the home to a seismometer. That sophisticated earthquake detector is part of a plan to carpet Alaska with like instruments about every 50 miles, from the Alaska Peninsula to Barrow.

The EarthScope Project is a traveling band of seismometers that has blanketed the continental states in past years. This summer, technicians and scientists have installed 20 stations in Alaska, including the one in Minto. Next year, workers with the National Science Foundation-funded project will try to install 40 more seismometers in some of the loneliest spots in Alaska and the Yukon. If that goes well, 80 more installations will follow in 2016.

With Alaska peppered with the stations, which will record earthquakes for a few years before most are removed and used elsewhere, seismologists hope to find out more about weak spots in Earth’s crust that slip to cause earthquakes. One of the more intriguing areas is the chain-of-lakes country outside the window of the Silases’ cabin.

Tape, a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Geophysical Institute, describes the Minto Flats seismic zone as a bowl of jellied soil the size of Mt. Everest. He is quite happy for the new seismometer at the Minto airport. It will help him and other scientists understand more about faults beneath the swampy, self-healing surface. When the ground slips there, it produces earthquakes like the magnitude 5.0 that happened 10 miles east of Minto on Aug. 30, 2014.

“In the past, you’ve had earthquakes in this region 1,000 times larger than two weeks ago,” Tape told 25 students in the Minto school before he walked over to knock on the door of Bergman and Sarah Silas. Almost every kid in the class had a story about the recent earthquake. One girl said her parents thought a tree had fallen on their one-story cabin.

At the Silas home, Tape was recording Bergman and Sarah’s stories of the 1947 earthquake, a magnitude 7.2. The Silases, married 70 years, both remembered intense shaking where they lived then on the Tanana River, at a site about 25 miles away known as Old Minto. Villagers moved from Old Minto to here above the Tolovana River flats in 1969. With the relocation, Bergman Silas said, they entered a world with electricity, TVs and telephones.

“Before, we just lived by telling stories,” Bergman said.

Now, the village of Minto has a scientific device that hears the Earth from beneath airport gravel. The instrument will record the passage of four wheelers, the tire bumps of the mail plane from Fairbanks and tremors in the ground from the restless lake country to the east. Seconds after earthquakes happen, scientists in Fairbanks and around the world will be able to see them for the first time with such exquisite detail.

Since the late 1970s, the director of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks has supported the writing and free distribution of this column to news media outlets. 2014 is Ned Rozell’s 20th year as a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.