Detail of portrait of Shoshoni Chief Tendoi Demonstrating Sign Language. (Photo by Charles M. Bell, circa 1880, courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.)

In early September 1930, the Blackfeet Nation of Montana hosted a historic Indian Sign Language Grand Council, gathering leaders of a dozen North American Nations and language groups.

The three-day council held was organized by Hugh L. Scott, a 77-year-old U.S. Army General who had spent a good portion of his career in the American West, where he observed and learned what users called Hand Talk, and what is today more broadly known as Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL). With $5,000 in federal funding, Scott filmed the proceedings and hoped to produce a film dictionary of more than 1,300 signs. He died before he could finish the project.

Scott’s films disappeared into the National Archives. Recently rediscovered, they are an important resource for those looking to revitalize PISL.

Among them is Ron Garritson, who identifies himself as being of Cree, Cherokee and European heritage. He was raised in Billings, Montana, near the Crow Nation.

“I learned how to speak Crow to a degree, and I was really interested in the sign language,” he said. “I saw it being used by the Elders, and I thought it was a beautiful form of communication. And so I started asking questions.”

Garritson studied Scott’s films, along with works by other ethnographers and now has a vocabulary of about 1,700 signs. He conducts workshops and classes across Montana, in an effort to preserve and spread sign language and native history.

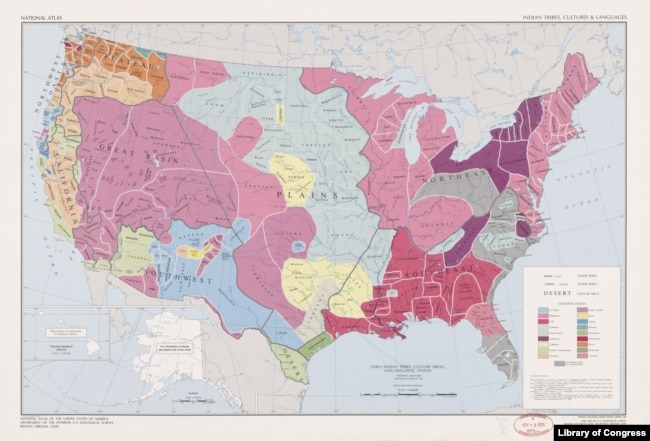

This map shows location of tribes, cultural areas and language groups prior to European contact.

Lingua franca

Prior to contact with Europeans, North American Native peoples were not a unified culture, but hundreds of different cultures and tribes, each with its own political organization, belief system and language. When speakers of one language met those of another, whether in trade, councils or conflict, they communicated in the lingua franca of Hand Talk.

Scholars dispute exactly when, in their 30,000-year history in North America, tribes developed sign language. It was observed among Florida tribes by 16th Century Spanish colonizers.

“Coronado, as he documented in his journals in 1540, was in Texas and met the Comanche,” said Garritson. “He documented that the Comanches made themselves so well-understood with the use of sign talk that there was almost no need for an interpreter. It was that easy to use and easy to understand.”[xyz-ihs snippet=”adsense-body-ad”]While each tribe had its own dialect, tribes were able to communicate easily. Though universal in North America, Hand Talk was more prominent among the nomadic Plains Nations.

“There were fewer linguistic groups east of the Mississippi River,” said Garritson. “They were mostly woodland tribes, living in permanent villages and were familiar with each other’s languages. They still used sign language to an extent, but not like it was used out here.”

Hand Talk was also the first language of deaf Natives.

Erasing a culture

By the late 1800s, tens of thousands of Native Americans still used Hand Talk. That changed when the federal government instituted a policy designed to “civilize” tribal people.

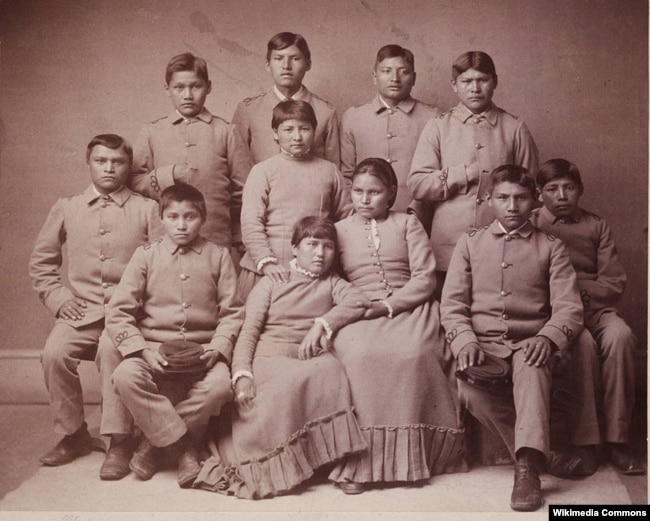

Photo portrait of Chiricahua Apache youths four months after arriving at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Children were removed from their families and sent to government-run boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their own languages or practice their own spiritual beliefs. Native Deaf children were sent to deaf residential schools, where they were taught to use American Sign Language (ASL).

Research has shown that Hand Talk is still being used by a small number of deaf and hearing descendants of the Plains Indian cultures.

“Hand Talk is endangered and dying quickly,” said Melanie McKay-Cody, of Cherokee descent, an expert in anthropological linguistics.

McKay-Cody is the first deaf researcher to specialize in North American Hand Talk and today works with tribes to help them preserve their signed languages. She is pushing for PISL to be incorporated into mainstream education of the deaf.

“Easier than hollering”

Lanny Real Bird, a Hidatsa Crow, grew up in a household where PISL was used.

“My grandmother had hearing loss,” he said. “I’d see my father signing with her in the Plains Indian Sign Language. I picked up basic sign language, enough to say, ‘Yes’ or ‘No,’ ‘I’m hungry.”

As a boy, he played with a young relative who was deaf, who helped expand his signing vocabulary.

Real Bird has worked for 20 years helping tribes preserve their languages, both spoken and signed, and has developed a 200-sign PISL course, which he teaches at community schools and workshops across the Plains states.

“Right now we’re probably at the basic communications phase,” he said. “So in order to expand, we have to go to another level, from listening to understanding to rudimentary communicating to fluency and literacy.”

Real Bird said it took nearly a decade to convince school systems to incorporate PISL into general language instruction.

“Later this month, students of the of the Crow Reservation’s Wyola Elementary School will be showcased at the annual Montana Indian Education Conference,” he said.

There, they will demonstrate their Crow language skills, both spoken and signed.

Source: VOA

[xyz-ihs snippet=”Adsense-responsive”]