At last week’s launch of World Bank’s Climate-Smart Mining Facility, NRDC elevates importance of place and community, citing reckless Pebble Mine as poster child for “wrong mine, wrong place.”

Last Wednesday in Washington, D.C., I was pleased to attend a gathering at the World Bank accompanying the launch of its climate-smart mining initiative—a public-private initiative based on the imperative that the realities of climate change and the accelerating transition to a green energy economy must become a central focus of present and future decision-making in the global mining sector.

Over the course of the full day meeting, representatives of mining companies, industry trade groups, mineral consumer industries, foreign mining and environmental agencies, international finance agencies, academic and research institutions, and environmental and human rights NGO’s offered a diversity of perspectives. From wind and solar power to storage batteries to recycling and urban mining to research and development, the focus of discussion was how to balance and prioritize the needs and risks associated with the extraction of minerals and metals essential to clean energy technologies and practices.

In a presentation to the gathering, I highlighted Northern Dynasty Minerals’ embattled Pebble Mine (“one of the most widely condemned mining projects anywhere”) as a poster child for unsustainable, climate-adverse mining—epitomizing a disregard for unreasonable risk and overwhelming community opposition that society in general and the mining industry specifically can’t afford and must no longer tolerate.

Indeed, the ubiquitous promotion of the project by Northern Dynasty (aka the Pebble Partnership) despite unanswered financial and technical concerns and the longstanding opposition of the people of the region—people committed to defending their communities, essential natural resources, economic livelihood, and cultural heritage from the reckless scheme—casts a dark shadow of disrepute on the entire mining industry.

The good news is that, for reasons of its unique financial, social, or environmental challenges, the project has already been abandoned by four of the world’s leading mining companies—Mitsubishi in 2011, Anglo-American in 2013, Rio Tinto in 2014, and First Quantum Minerals in 2018. The last company remaining is Northern Dynasty—now 100-percent owner of the project—a small underfunded, undiversified Canadian company that has itself unsuccessfully been trying to sell its interest since 2011.

But Northern Dynasty hasn’t given up, and the threat posed by the Pebble Mine remains.

This project represents in its starkest terms the need for that climate-smart mining to prioritize location and community, because, as I argued on Wednesday, “in discussing climate adaptation and mitigation, there’s no more important element—no more defining decision—than siting.” As unequivocally expressed in an extraordinary full-page bipartisan statement published in last Wednesday’s Washington Post: “The Pebble Mine is the wrong mine in absolutely the wrong place.”

More broadly, we must recognize the fundamental principle that there are some places on the planet that simply should not be mined—for reasons of financial, social, or environmental sustainability, and that includes climate-smart mining. Scientists now tell us, for example, that, to meet the Paris climate targets, we have to protect 50% of our terrestrial open space. As documented in a 1,500 page report released today by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services,

the health of ecosystems on which we and all other species depend is deteriorating more rapidly than ever. We are eroding the very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide. . . . This loss is a direct result of human activity and constitutes a direct threat to human well-being in all regions of the world.

With this in mind, can we really afford to turn the pristine Bristol Bay watershed into a massive mining district?

Scientists also tell us that our food production is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. Can we afford to risk a fishery that generates 50 percent of the world’s wild sockeye salmon—a food source whose carbon footprint is a small fraction of that of beef and other high carbon foods?

And can we afford to ignore the overwhelming opposition of the indigenous communities who depend on that fishery?

If we’re serious about climate-smart mining—if we’re serious about sustainable mining over the long term—the answer to such questions is no.

Disregard of the social and environmental problems that flow from the “wrong mine, wrong place” is a prescription for failure—a failure that the mining industry (and all of us who depend on it) will need to avoid. In the face of advancing climate change, this will be a critical indicator of whether, as a society, we have the common sense and good judgment to secure the survival of our planet.

The Trump Administration is currently fast-tracking the Pebble Mine through the permitting process. Take action now to stop the Pebble Mine.

My remarks at the World Bank’s conference follow:

You may have seen this extraordinary full-page statement in the Washington Post this morning—entitled “The Pebble Mine is the wrong mine in the wrong place”

It’s extraordinary not just because of the clarity of its content but because of who signed it:

The Interior Secretary from the Clinton Administration and EPA Administrators from the Presidencies of Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, George HW Bush, and George W. Bush.

It’s wonderfully bi-partisan—and it’s relevant here because, in discussing climate adaptation and mitigation, there’s no more important element—no more defining decision—than siting.

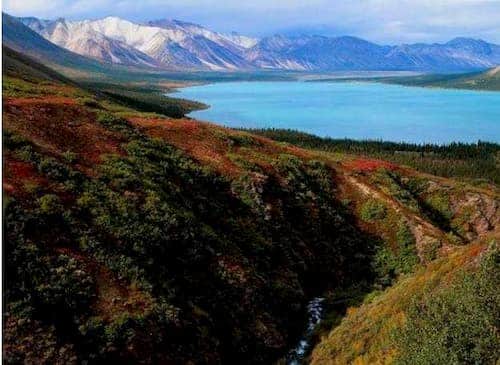

And there’s no better current case study for why this matters than the Pebble Mine—proposed for construction in the Bristol Bay region of southwest Alaska, in the headwaters of the greatest, most productive wild sockeye salmon fishery on Earth.

That single fishery produces 50 percent of the world’s wild sockeye salmon, including over 62 million fish last summer alone.

It generates 1.5 billion in revenue every year and 14,000 jobs.

It’s a powerful economic engine that, for generations, has sustained southwest Alaska and its people.

It’s the wrong place for large scale mining, and the Pebble Mine has been relentlessly opposed for over a decade by 80 percent of the region’s residents—tribes, village associations, commercial fishermen, recreational fishermen, hunters, businesses, conservationists, the multi-billion dollar BBNC, BBNA, BBEDC, and many more.

For a sense of the region’s resolve, just take a look at the Vancouver Sun ad on the right of the screen.

The Pebble Mine truly is the “wrong mine in the wrong place,” and, over the past decade, it has become one of the most widely condemned mining projects anywhere.

But here’s the good news:

In 2011, Mitsubishi sold out.

In 2013 Anglo American walked away.

In 2014, in a stroke of brilliant community engagement, Rio Tinto donated all of its shares to two Alaskan non-profits.

And in 2018 First Quantum Minerals became the latest to abandon its interest.

The good news is that this project failed to meet their standards for financial, social, or environmental sustainability.

The good news is that these four leading mining companies heard the people of Bristol Bay and listened to them.

And there’s more:

In 2014, based on a three-year scientific risk assessment requested by Alaskan tribes, EPA found that large scale mining like Pebble cld have “catastrophic” impacts on the region.

In 2016, by a virtually unanimous vote, the IUCN’s World Conservation Congress condemned the project.

In 2018 Tiffany & Co. reaffirmed its No Pebble Pledge—endorsed by some 60 jewelry companies around the world—that they wld never source from Pebble if it’s built.

In 2019—just last week—Whole Foods, Patagonia, and 200 other businesses called for suspension of the federal permitting process.

Here’s the fundamental point:

There are some places on the planet that simply shld not be mined—

for reasons of financial, social, or environmental sustainability, and that includes the imperative of climate-smart mining.

Scientists now tell us that, to meet the Paris goals, we have to protect 50% of our terrestrial open space:

With this in mind, can we really afford to turn the pristine Bristol Bay watershed into a massive mining district?

Scientists tell us that our food production is a major contributor to GHG emissions.

With this in mind, can we afford to risk a fishery that generates 50 percent of the world’s wild sockeye salmon—a low carbon food source whose carbon footprint is a small fraction of that of beef?

Can we afford to ignore the overwhelming opposition of the indigenous communities who depend on that fishery?

I say we can’t, and I hope you do too.

Because this will determine whether, as a society, we have the common sense and good judgment to secure the survival of our planet.

This will determine whether the mining industry—and all of us who depend on it—are serious about climate smart mining.