WASHINGTON — In December 1900, John Wesley Powell received “the most unusual Christmas present of any person in the United States, if not in the world,” reported the Chicago Tribune.

The gift for this first director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of Ethnology was a sealskin sack containing the mummified remains of an Alaska Native.

The sender was a government employee hired to hunt Indian “relics,” who said the remains had been difficult to acquire because “to come into the possession of a dead Indian is a great crime among the Indians.”

The report concluded that it was the only “Indian relic” of this kind at the Smithsonian and it was “beyond money value.”

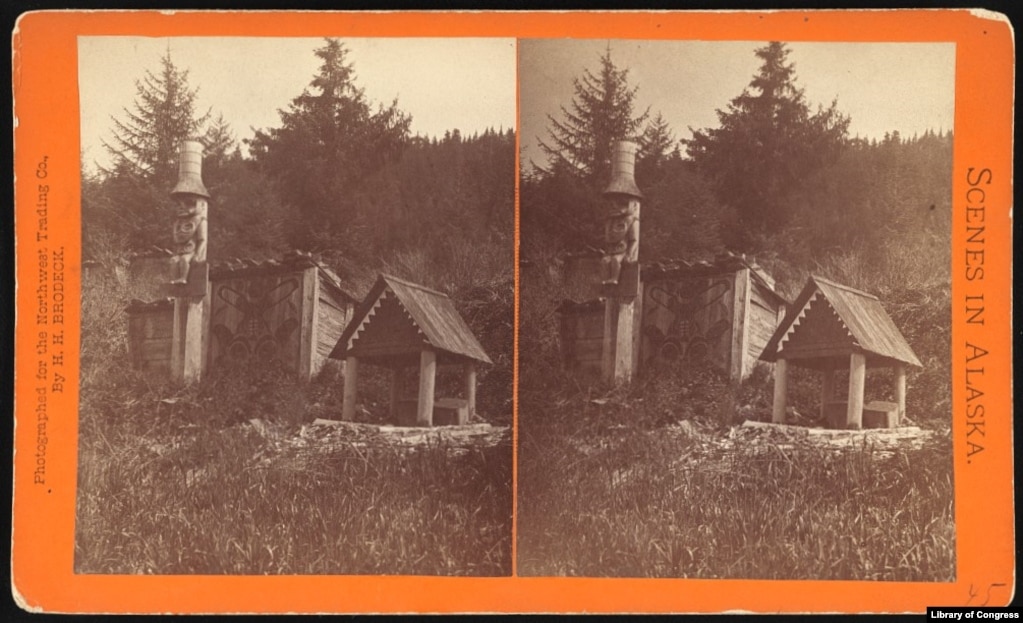

As it turned out, it was not the museum’s only Alaskan mummy. In 1865, even before the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia, Smithsonian naturalist William H. Dall was hired to accompany an expedition to study the potential for a telegraph route through Siberia to Europe. In his spare time, he looted graves in the Yukon and caves on several Aleutian Islands.

After the U.S. sealed the deal with Russia, the San Francisco-based Alaska Commercial Company won exclusive trading rights and established more than 90 trading posts in Alaska to meet the U.S. demand for ivory and furs.

It also instructed agents “to collect and preserve objects of interest in ethnology and natural history” and forward them to the Smithsonian. Ernest Henig looted 12 preserved bodies and a skull from a cave in the Aleutians in 1874. He donated two to California’s Academy of Science and sent the remainder to the Smithsonian.

More than 30 years after the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act meant to return those remains, a ProPublica investigation last year estimated that more than 110,000 Native American, Native Hawaiian and Alaska Native ancestors remain in public collections across the U.S.

Pages: 1 2