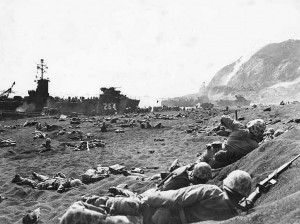

On February 19, 1945, 20-year-old Bill Young of Mooresville, North Carolina, disembarked an LST on a miserable hunk of black rock called Iwo Jima. He was part of a 75-mile-long convoy of ships preparing to dislodge the Japanese from this volcanic remnant of an island. The territory was formally part of Japan, meaning it was considered literal sacred ground to Japanese soldiers.

Just how many Japanese were there, and where, was a mystery to Bill and the approaching Marines. It took his crewmen six weeks to arrive. They slept in cots under a tarp erected on the deck; all beds below were taken up by as many men as the U.S. military could jam on one boat. But that little bit of discomfort was nothing compared to what was unexpectedly awaiting them.

“The plan was to be at Iwo Jima just a few days to mop it up—less than a week we were told,” Bill told me. They would tidy up things and then move on. The Japanese, however, had other plans.

“I ended up there for 37 days,” says Bill, who stayed for the full duration of the unforeseen hell ahead. “We ran into more resistance than we ever thought imaginable. It was a real killing field.”

It became the bloodiest battle for American troops during all of World War II, with 7,000 killed and 20,000 casualties. Bodies, bullets, and death everywhere.

“You could just shoot into a crowd and kill someone, there was so many people,” says Bill of those first waves that stormed the beaches. “We lost one Marine every 45 seconds, more than one per minute, for the first three days. We didn’t have anywhere to bury them. We laid them out side by side, put a raincoat over them until we could build a cemetery.”

I asked Bill about those early moments. In his low-key voice, he recalled that things happened so fast he didn’t have time to dwell on the calamity. In between firing their weapons, he and the others tried to make foxholes but couldn’t because of the odd lava rock. Their instinct was to simply survive.

The Japanese weren’t on the island, explains Bill, they were in the island. They were hidden in a wild labyrinth of caves, intricate tunnels, and camouflaged concealments.

The Japanese dead numbered around 19,000, with only about 200 taken prisoner—those too injured to kill themselves with their grenades. The Japanese homeland was only 600 miles away. They would (and did) fight to the death. And they took a lot of good American boys with them.

As for Bill, he survived without a scratch, but most weren’t so fortunate. Of the six men who raised the famous flag photographed atop Mount Suribachi, only three left the island, with two of them, John Bradley and Rene Gagnon, going on to lead normal lives. Bradley is the subject of the superb book-turned-film, Flags of Our Fathers. The third surviving flag raiser was Ira Hayes, a Native American.

Bill Young knew Ira Hayes. He vividly remembers leaning on the ship rail and shooting the breeze with Ira for several hours on the boat home. “They didn’t think nothing of it,” says Bill of Ira and his fellow flag-raisers. “They just grabbed a pipe, put a flag on it, and raised it.”

But everyone else thought something of it. The moment was captured by AP photographer Joe Rosenthal and became a national sensation. Indeed, Ira’s time with Bill on the ship was cut short when a helicopter nabbed the instant celebrity to rush him off to sell war bonds. He and Bradley and Gagnon became a huge hit touring the country.

The adulation, however, couldn’t heal Ira Hayes, who used alcohol to cope with the horrors he experienced. He died a sad death after returning home.

Bill Young didn’t get home right away. He readied for an even worse dénouement with the devil: an invasion of Japan’s mainland. He was spared when President Harry Truman dropped the atomic bomb, finally compelling the Japanese to surrender.

Bill Young eventually made his way home. He married his sweetheart, Arvelle. They were together for 58 years before her death. Today, at age 90, Bill lives next door to the house where he grew up.

Asked how he feels about his time in World War II, Bill recalls the entire experience, beyond just Iwo Jima, and says simply: “I’m glad I did it. I enjoyed it, as much as you could something like that.”

Yes, as much as you could enjoy something like that.

Iwo Jima was, says Bill Young, a real killing field. On the anniversary of that ferocious battle, let’s remember Bill and all those who sacrificed so much.