[content id=”79272″]

Using a combination of survey data and laboratory studies, NOAA Fisheries scientists identified starvation as the most likely cause of mass mortality event during the eastern Bering Sea marine heatwave.

In 2022, the Alaska snow crab fishery was closed for the first time in history due to a sudden, dramatic decline in adult and juvenile crabs. Scientists now believe the most likely cause of the decline was starvation and other factors linked to the 2018-2019 marine heatwave.

“During the marine heatwave, snow crabs faced a triple threat,” said lead author and Alaska Fisheries Science Center stock assessment scientist Cody Szuwalski. “Their metabolism increased, so they needed more food; their habitat was reduced so there was less area to forage; and crabs caught in our survey weighed less than usual. These conditions likely set them up for the dramatic decline we saw in 2021.”

The mortality event appears to be one of the largest reported losses due to marine heatwaves among the groups of animals that include fish and crustaceans globally.

Crab Abundance: Historic High to Record Low

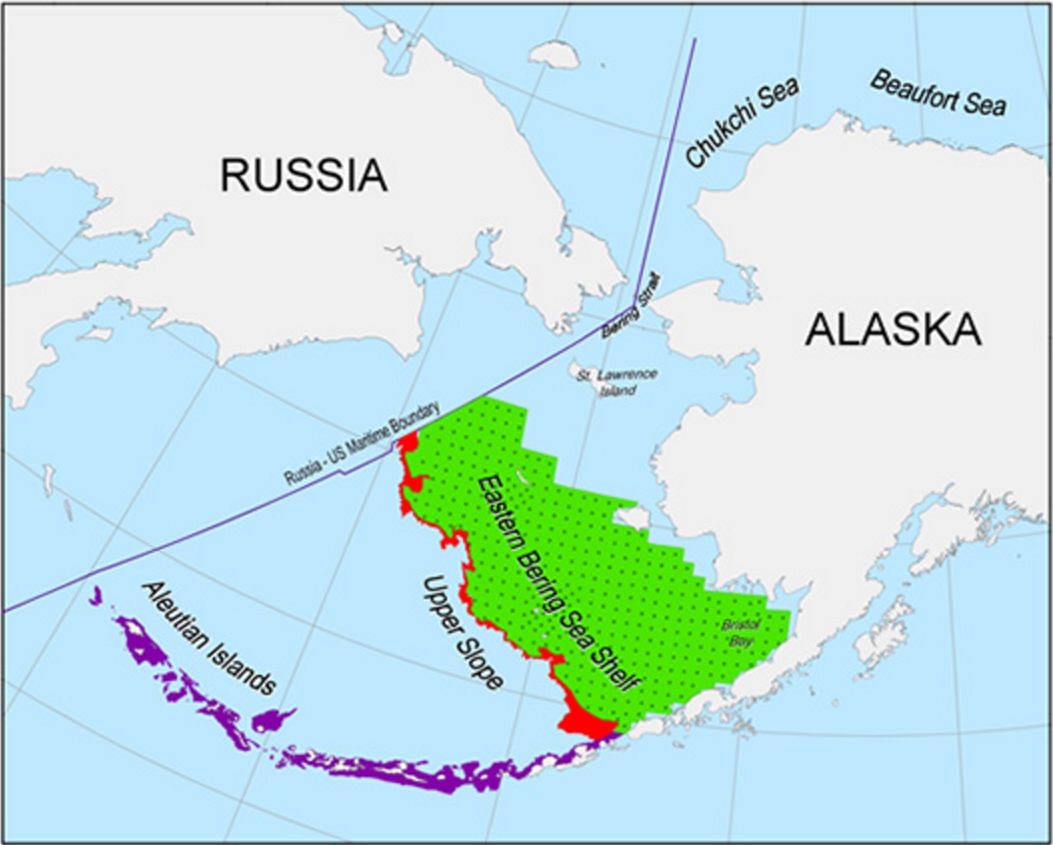

In 2015, NOAA Fisheries scientists reported seeing a record number of juvenile snow crabs during their annual research survey in the eastern Bering Sea.

But just 3 years later that picture had changed. Between 2018 and 2019, the abundance of juvenile snow crabs declined by roughly half. By 2021, the survey found the fewest snow crab on the eastern Bering Sea shelf since the survey began in 1975. More than 10 billion crab disappeared from this region in the period 2018 to 2021.

Snow crab is one of the most abundant species in the bottom-dwelling ecosystem of the eastern Bering Sea. It supports an important commercial fishery, generating an average $150 million annually from 2012 to 2021. In 2021, 59 boats fished for snow crabs and brought $219 million into fishing communities.

As a result of the population decline, the state of Alaska subsequently announced the closure of the commercial snow crab fishery for the 2022–2023 season.

St. Paul, Alaska, home to the largest processing plant for crab in the world, was hit hard. A largely Indigenous community, St. Paul is highly dependent on the snow crab fishery. As a result of the fishery closure, Saint Paul declared a cultural, economic, and social emergency.

The Secretary of Commerce announced Disaster Declarations 2022–2023, which afforded some disaster relief funds to fishing communities.

The Looming Question: What Caused the Snow Crab Decline?

In this study, scientists considered factors that cause mortality such as:

-

Directed fishing

-

Bycatch in commercial trawls

-

Cannibalism

-

Predation from Pacific cod

-

Disease

-

Increased temperatures

In particular, they didn’t see a strong connection between variability in snow crab mortality, and predation and bycatch.

Pacific cod predation was near average levels during the collapse. For half of 2018, a large fraction of the cod population moved out of the eastern Bering Sea into the northern Bering Sea— a rare occurrence. This movement may have decreased the already average predation on snow crabs.The missing snow crabs were also larger than cod normally eat.

Scientists also ruled out bycatch as a significant factor in the snow crab decline for a couple of reasons. Trawling activity in the Bering Sea has been relatively consistent over the last two decades. The observed bycatch of snow crab by trawlers was actually much lower than historical levels. The largest group of young crab in history was observed in surveys and grew on the sea shelf for about eight years under consistent trawling pressure before the collapse.

“All of these factors cause some mortality, but only temperature and population size could explain the increase in mortality during the heatwave on such a scale in our models. High temperatures and large population sizes suggest

starvation was a likely cause of the decline,” said Szuwalski.

Snow Crab Metabolism Speeds Up with Warmer Water Temperatures

NOAA Fisheries scientists have observed ocean temperatures over the 40-year history of their annual bottom trawl survey of the eastern Bering Sea. In 2018 and 2019, they observed ocean temperatures that were well above average. This marine heatwave was associated with die-offs of a number of species including ice-associated seals and seabirds.

Despite these unprecedented marine heatwave conditions, ocean temperatures were still within the upper extent of what snow crab could tolerate. But, scientists suspect that the warmer water temperatures affected snow crab metabolism.

Scientists, through lab tests, demonstrated that snow crab metabolism increases under rising water temperatures. For example, the caloric requirements for snow crab in the lab nearly doubled in water temperatures ranging from 0 to 3 degrees Celsius. This is roughly the change experienced by immature crab in the eastern Bering Sea from 2017 to 2018.

Prey Limitations and Reduced Habitat Likely Affected Snow Crab Condition and Survival

Data collected during research surveys on the weight of various ages of juvenile snow crab support the hypothesis that young crab were not getting enough to eat. In 2017, a crab with a 75-millimeter-wide shell weighed 156 grams on average. In 2018, this same size crab was roughly 25 grams lighter, weighing around 104 grams— a 15 percent decline in body weight.

Scientists also looked at the size of the area where the snow crabs were captured during their 2018 research survey. They noted that the crab was being caught in a smaller area than normal—the smallest relative to historic habitat in the history of the survey.

“The unprecedented caloric demands coupled with a small area from which to forage relative to historical grounds provide more evidence to support the model conclusions that starvation likely played a key role in the snow crab decline. This event mirrors what happened to Pacific cod in the Gulf of Alaska in 2016 during a marine heatwave,” said Mike Litzow, director, Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s Kodiak Lab. “We also suspect some cannibalism was occurring given the overlap between adult and juvenile crabs in the same small area.”

Adapting to Changing Ocean Conditions

Brian Garber-Yates is an economist from the Alaska Fisheries Science Center and another co-author on the paper. He suggests that resource managers’ best defense against continued warming conditions and future marine heatwaves is to enable the fishing industry to diversify.

There are a number of ways managers can respond to changing crab and fish stock abundance, including:

- Improving efficiency in the distribution of disaster relief funds

- Providing increased flexibility to allow fishermen to pursue diverse portfolios of species

- Ensuring consistent and timely biological surveys

- Supporting the development of alternative marine-based livelihoods, such as mariculture

Scientists can help, too, by providing timely data and information and near-term and future projections to help managers and fishermen better anticipate and plan for what lies ahead. Modeling projects and continued delivery of ecosystem information, which aid our understanding of how the changing environment is impacting marine resources, are instrumental in this effort. Some of these resources include ACLIM and GOACLIM, part of NOAA Fisheries Climate-Ready Fisheries Initiative, and Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s ecosystem status reports.

“Current management tools base projected sustainable yields of fish catches on the historical dynamics of a population,” said Szuwalski. “However, projections based on historical dynamics are not reliable when the future of a region doesn’t resemble the past.”

[content id=”79272″]