The Kremlin reiterated its intention to field a formidable combined arms force to protect its political and economic interests in the Arctic by 2020. Going into 2015, it is estimated that the Russian armed forces have around 56 military aircraft and 122 helicopters in the Arctic region. Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu stated that 14 military airfields on Russia’s Arctic seaboard would be operational by the end of the year. The Ministry of Defense also said some of the 50 modernized MiG-31BM Foxhound interceptors expected by 2019 will be charged with defense duties over the Arctic. Despite the economic problems plaguing Russia, the Ministry of Defense managed to escape the significant budget cuts levied against most other ministries. In fact, the Kremlin has increased defense spending by 20 percent, a clear indication of Russia’s priorities for 2015 and a likely indication that Moscow intends to meet its military commitments.

The Kremlin reiterated its intention to field a formidable combined arms force to protect its political and economic interests in the Arctic by 2020. Going into 2015, it is estimated that the Russian armed forces have around 56 military aircraft and 122 helicopters in the Arctic region. Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu stated that 14 military airfields on Russia’s Arctic seaboard would be operational by the end of the year. The Ministry of Defense also said some of the 50 modernized MiG-31BM Foxhound interceptors expected by 2019 will be charged with defense duties over the Arctic. Despite the economic problems plaguing Russia, the Ministry of Defense managed to escape the significant budget cuts levied against most other ministries. In fact, the Kremlin has increased defense spending by 20 percent, a clear indication of Russia’s priorities for 2015 and a likely indication that Moscow intends to meet its military commitments.

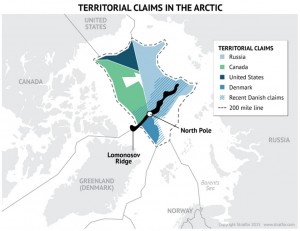

At the end of 2014, Russia established a unified strategic command based around the existing command architecture of the Northern Fleet. The force structure successfully facilitates a military reach across the islands of Russia’s northern territories, allowing for better oversight and control of the trade route from China to Norway. This structure also serves the purpose of monitoring — and potentially checking — any military moves by any other power in the region.

Along with the Baltic states and their respective environs, the Barents Sea is under constant surveillance by Russian fighter jets. Russia’s dominance in the region was further solidified when, in late December, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a new military doctrine. In stark contrast to previous dictums, the Arctic region was officially put on the list of Russian spheres of influence for the first time. The same recognition applies to Russia’s maritime doctrine, which has two major geopolitical imperatives: a thrust toward the Black Sea and dominion of the near Arctic.

The Norwegian Response

Although Russia’s planned expansion in the Arctic may appear aggressive, military authorities in the Kremlin have no desire for an armed confrontation with Western powers. Moscow is aware of NATO’s Article 5 agreement, which states that any attack on an individual member country could invoke a unified response from the alliance. Nevertheless, the increased Russian military presence in the region makes neighboring countries uneasy, particularly Norway.

Russia’s actions in Ukraine, along with its military exploitation of the Arctic, forced Oslo to reassess Moscow’s role and intent in the north, specifically in the area of the Barents Sea. Norway backed the Western application of sanctions against Russia, and subsequent motions from Oslo reveal a major shift in the country’s strategic perception of Russia as a potential threat, in addition to highlighting the smaller country’s inherent vulnerabilities. Yet, Norway is a leader when it comes to promoting NATO’s role in the Arctic; it is the only country in the world that has its permanent military headquarters above the Arctic Circle. Although Norway contributed troops to the multinational force in Iraq and more than 500 personnel to the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan — and was one of only seven NATO members to actually carry out air strikes during the Libya campaign — the primary force driver for its military is Arctic security. The Norwegians have invested extensively in Arctic defense capabilities, but, in terms of size and means, they are dwarfed by Russia. Because of this, Norwegian officials, both military and civilian, want to see NATO play a larger role in the Arctic.

Despite a tenuous degree of military cooperation between Norway and Russia in the past involving visits of military officials and occasional joint exercises, conventional wisdom dictated that Oslo did not hold any military exercises near its border with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. This reticence continued after the fall of the Iron Curtain, yet the Norwegian government recently announced its intent to conduct large-scale drills in Finnmark — a territory on the Russia-Norway border — in March 2015. The proposed maneuvers will be the country’s largest military exercises since 1967. There is a growing recognition in Moscow that Norway’s policy toward Russia is going through a major shift as a direct reaction to Moscow’s push to militarize the Arctic region.