Scientists and others from remote communities across western Alaska and northern Canada concerned about the migration of beavers into the Arctic will gather at the University of Alaska Fairbanks later this month.

Attendees will share observations, knowledge and new research on the impacts of the animals’ recent range expansion.

The Feb. 26-28 meeting of the Arctic Beaver Observation Network will be at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Participants will come from Canada, the United Kingdom, Norway and elsewhere in the United States.

This will be the third meeting of the group, which last met in Yellowknife, in Canada’s Northwest Territories, in November 2022.

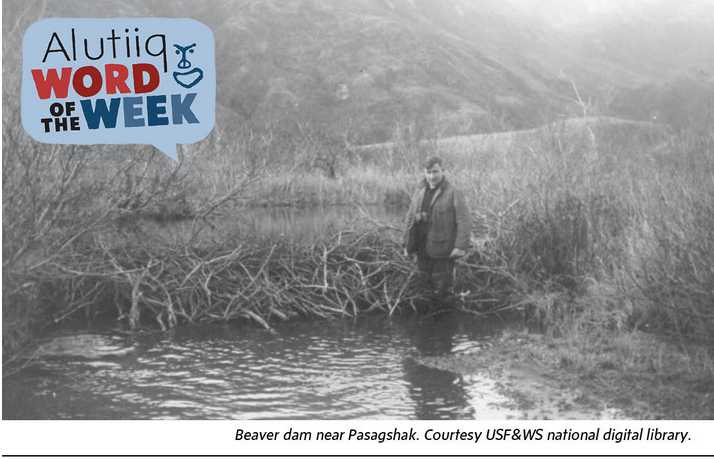

Beavers have been damming Arctic streams in Alaska and other Arctic regions, creating numerous ponds. The ponds thaw permafrost, releasing carbon that would otherwise remain locked in place in undisturbed permafrost. Deeper and warmer pond water alters stream ecology and provides an environment where new species can survive the winter.

“If you ask the people in remote communities, this is an issue that has come up time and again, so addressing it is overdue,” said UAF associate professor Ken Tape, who is leading the project. “Land managers are also paying attention since beavers affect the resources that a given landscape supports.”

Tape has been researching the impact of the beavers’ northern migration for several years.

Research by Tape and his group published in 2018 included observations indicating beaver movement from forest into tundra of western and northwestern Alaska and northwestern Canada. The northern edge of beaver distribution has historically been limited to forested areas.

Research associate professor Benjamin Jones of the UAF Institute of Northern Engineering is helping lead the work, along with Caroline Brown, research director with the Subsistence Division of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in Fairbanks.

“Communities participating in this project have been observing these changes for a while,” Brown said. “Their insights about changes to travel routes and access for subsistence hunting and fishing are an important part of this project.”

The meeting will cover several topics over three days, including updated information on where beaver engineering is occurring; its effect on fish, water quality, biodiversity, permafrost and wildfire; local community observations and impacts; and management options.

“Scientists are interested in how beavers are reshaping lowland ecosystems, both aquatic and terrestrial, and whether those changes accelerate or buffer against the ongoing effects of climate change,” Tape said. “Without a clear understanding of this issue, there is no way to know what an Arctic stream corridor will be like in 20 years when beavers arrive. Or yesterday, if they’re already there.”

The Arctic Beaver Observation Network is funded by the National Science Foundation. The five-year project runs through 2026. The network consists of scientists, local observers, land managers, tribal representatives and other stakeholders.

“For an issue as multifaceted as this one, understanding can only come from a synthesis of a variety of perspectives,” Tape said. “As such, the format of the meeting is more open and encouraging of discussion rather than the usual series of focused, technical presentations.”

[content id=”79272″]