Outreach video produced on the occasion of the publication in the scientific journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS) of the paper entitled “Multiwavelength observations of a bright impact flash during the January 2019 total lunar eclipse”, by J.M. Madiedo, J.L. Ortiz, N. Morales and P. Santos-Sanz.

Observers watching January’s total eclipse of the Moon saw a rare event, a short-lived flash as a meteorite hit the lunar surface. Spanish astronomers now think the space rock collided with the Moon at 61,000 kilometers an hour, excavating a crater 10 to 15 meters across. Prof Jose Maria Madiedo of the University of Huelva, and Dr Jose L. Ortiz of the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, publish their results in a new paper in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Total lunar eclipses take place when the Moon moves completely into the shadow of the Earth. The Moon takes on a red color – the result of scattered sunlight refracted through the Earth’s atmosphere – but is much darker than normal. These spectacular events are regularly observed by astronomers and the wider public alike.

The most recent lunar eclipse took place on 21 January 2019, with observers in North and South America and Western Europe enjoying the best view. At 0441 GMT, just after the total phase of the eclipse began, a flash was seen on the lunar surface. Widespread reports from amateur astronomers indicated the flash – attributed to a meteorite impact – was bright enough to be seen with the naked eye.

Madiedo and Ortiz operate the Moon Impacts Detection and Analysis System (MIDAS), using eight telescopes in the south of Spain to monitor the lunar surface. Video footage from MIDAS recorded the moment of impact.

The impact flash lasted 0.28 seconds and is the first ever filmed during a lunar eclipse, despite a number of earlier attempts.

“Something inside of me told me that this time would be the time”, said Madiedo, who was impressed when he observed the event, as it was brighter than most of the events regularly detected by the survey.

[content id=”79272″]

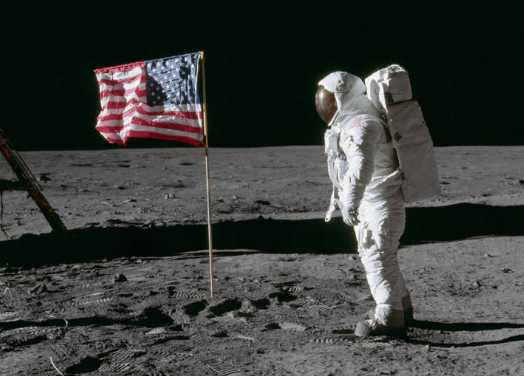

Unlike the Earth, the Moon has no atmosphere to protect it and so even small rocks can hit its surface. Since these impacts take place at huge speeds, the rocks are instantaneously vaporized at the impact site, producing an expanding plume of debris whose glow can be detected from our planet as short-duration flashes.

MIDAS telescopes observed the impact flash at multiple wavelengths (different colors of light), improving the analysis of the event. Madiedo and Ortiz conclude that the incoming rock had a mass of 45kg, measured 30 to 60 centimeters across, and hit the surface at 61,000 kilometers an hour. The impact site is close to the crater Lagrange H, near the west-south-west portion of the lunar limb.

The two scientists assess the impact energy as equivalent to 1.5 tonnes of TNT, enough to create a crater up to 15 meters across, or about the size of two double-decker buses side by side. The debris ejected is estimated to have reached a peak temperature of 5400 degrees Celsius, roughly the same as the surface of the Sun.

Madiedo comments: “It would be impossible to reproduce these high-speed collisions in a lab on Earth. Observing flashes is a great way to test our ideas on exactly what happens when a meteorite collides with the Moon.”

The team plan to continue monitoring meteorite impacts on the lunar surface, not least to understand the risk they present to astronauts, set to return to the Moon in the next decade.

###

Source: Royal Astronomical Society