Kapsuutait cetertaallkait. – They used to mark their spears.

The Alutiiq verb ceterluni can mean either to mark or to scratch. Today, some of the Alutiiq words for pencil, pen, and even signature are related to this term. In the past, however, ceterluki probably referred to making ownership marks. Across the north, coastal peoples identified their property with such marks. Men and women painted, carved, cut, and sewed special designs into objects to show they belonged to a person, a household, or a family. Ownership marks typically used a few lines to create a simple design. People placed them on many items, from bowls and buckets to parkas, but they were most common on hunting and fishing gear.

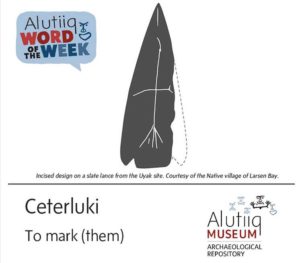

Archaeological finds from Kodiak suggests that Alutiiq ancestors used ownership marks at least 6,500 years. Early designs include a pair of parallel diagonal lines, a pair of perpendicular crossed lines, an X, a long Y, or a series of short, parallel, horizontal lines purposefully cut into one side of the lance. Over time, the designs become more varied. Simple lines are present, but there are also geometric designs, circles, arched lines, and motifs that may represent feathers or skeletons. One lance head has a band of incised design that resembles parka embroidery—a series of small dots between a pair of parallel lines. A few designs have recognizable silhouettes—an aerial view of a harpooned sea mammal, a bird’s footprint, or a person.

Ownership marks helped hunters maintain respectful relationships with animal spirits and ensure future harvesting success. In the Alaska Native world, animals give themselves to harvesters who act respectfully. A respectful hunter never kills an animal without retrieving its body. Ownership marks helped each hunters take proper care of the animals they harvested.

Source: Alutiiq Museum