Photo by Ned Rozell.

The revival of the virus responsible for the 1918 Spanish flu, the killer of millions of people, was the end of a long journey for Johan Hultin. Hultin, 90, twice retrieved samples of the virus from the lungs of flu victims preserved by permafrost in an Alaska village. Molecular pathologists used the latter of those samples to reconstruct the virus and discover that it jumped from birds to humans.

Hultin visited the village of Brevig Mission, on Alaska’s Seward Peninsula, on two separate missions nearly half a century apart. He wanted to find what he describes as “the most lethal organism in the history of man.”

Hultin was studying microbiology at the University of Iowa in 1949 when a virologist there mentioned that the key to understanding the long-gone Spanish flu of 1918 may be frozen in the bodies of flu victims buried in permafrost. Those victims could possibly be found in Alaska, where “Spanish influenza did to Nome and the Seward Peninsula what the Black Death did to fourteenth-century Europe,” wrote Alfred Crosby in The Forgotten Pandemic.

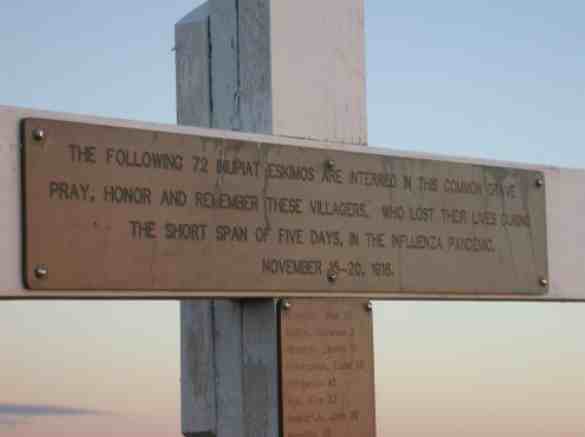

In 1951, Hultin traveled to Brevig Mission. There, in 1918, the Spanish flu killed 72 of the 80 people, 90 percent the village, from Nov. 15-20, 1918. The deadly virus may have reached the village on the breath of men bringing supplies to the nearby village of Teller. Brevig Mission Natives who loaded their dogsleds with supplies there might have picked up the virus by working beside the men.

After the sudden fatalities at Brevig Mission, officials of the territorial government hired gold miners from Nome to dig a grave large enough for 72 people. Driving steam points into the permafrost on a hillside near the village, the miners thawed a hole 12 feet wide, 25 feet long, and about six feet deep. The bodies buried there remained somewhat preserved by the frozen soil surrounding them.

When Hultin arrived in 1951, with the permission of the village elders he built a fire on the ground surface to thaw the permafrost beneath. Then he shoveled off the melted soil, exposed the new surface to air, and repeated the process.

“It was a lot of work,” Hultin said from his home in San Francisco. “It took two days to reach the first body.”

Hultin removed lung tissue from the body and brought it back to the lab in Iowa City. Try as he and his colleagues might, they could not revive the virus nor gain any insight into what made it so deadly.

Forty-six years later, Hultin read an article in the journal Science written by Jeffery Taubenberger, a molecular pathologist who was looking for samples of the flu virus to supplement tiny samples saved from two young soldiers in 1918.

Using $3,200 from his savings account, Hultin at age 72 traveled back to Brevig Mission in 1997. There, with the help of four Native boys, he once again opened the mass grave. He removed the preserved lungs of a woman who had died from the flu, and shipped them to Taubenberger?s lab in Washington, D.C.

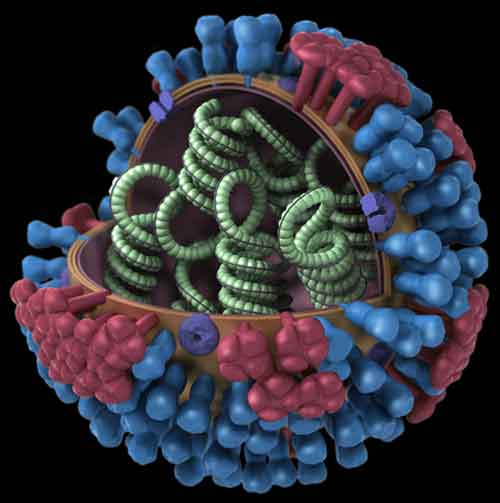

Using the samples, in 2005 Taubenberger and his colleagues reconstructed the 1918 virus and revealed that it originated in birds and mutated to infect people. Virologists have called it the largest breakthrough in years, a discovery that could save many lives. Hultin remains humble about his role.

“I’m very fortunate to have been at the right place at the right time,” Hultin said.

Since the late 1970s, the director of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks has supported the writing and free distribution of this column to news media outlets. This is Ned Rozell’s

20th year as a science writer for the Geophysical Institute. This column first appeared in 2004.