Litnaurluni–Study

Litnauryugtuci-qaa?–Do you all want to study?

The study of Alutiiq heritage has changed dramatically in the past three centuries. In classical Alutiiq society, children learned the skills of adult life by working with and listening to family members. People with special gifts—artists, healers, shamans, tradition bearers, and politicians—apprenticed to accomplished community members to study a trade. An aspiring midwife would assist an established healer, or a rising leader might work as a member of the chief ’s council or a community’s second chief to enhance his knowledge of diplomacy.

This intergenerational transmission of traditions eroded in the historic era as European practices and values collided with Alutiiq culture. Some Alutiiq traditions disappeared due to social pressure. For example, Alutiiq people stopped wearing labrets within decades of conquest, because facial piercing horrified European colonists. Other traditions were systematically suppressed with western instruction. In American-era schools, children were forbidden to speak Alutiiq and received instruction in English. On Woody Island, missionaries teaching Alutiiq boys to play baseball made them speak in English. When they used Alutiiq or Russian they had to sit out the game. More serious discipline included physical punishment and humiliation.

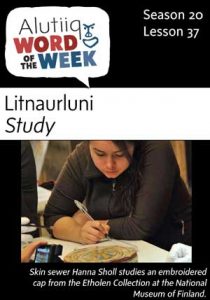

Today, the formal study of Alutiiq heritage is returning to Kodiak. Many of the islands’ schools recognize and celebrate Native heritage by including Alutiiq cultural exploration in classroom curricula and by hosting programs that teach Alutiiq heritage in Alutiiq ways. Other education programs are thriving through local organizations. The Alutiiq Museum’s language program pairs fluent Alutiiq speakers with apprentices to reawaken Kodiak’s Native language. This work is helping to revitalize the transfer of traditional knowledge from one generation to the next.

Source: Alutiiq Museum[xyz-ihs snippet=”Adsense-responsive”]