Wow, do Alaskans love bats! Last week’s column on little brown bats inspired three times the comments I usually get.

People rang in with bat sightings from Nikiski to North Pole; a few offered up their secret spots to scientists who might want to study bats.

Jesika Reimer, a bat expert and consultant who lives in Anchorage, has in the past taken people up on those offers. Reimer has held in her hands little brown bats from the Northwest Territories to the Tanana River. Along with a few colleagues around Alaska, she is sharing new information about the farthest-north bat.

She said this palm-size creature that weighs as much as a quarter lives more than twice as long as your dog: from 35 to 40 years.

Mama bats, now hanging out there in some unknown chilly space, are storing the sperm they received during mating swarms a few weeks ago. If things go well this winter, the females will emerge next spring with a tiny fetus growing within them. They have only one pup each summer.

In early spring, mother bats suddenly appear in large maternity roosts. Alaskans have noticed bats flying in midsummer from notches in the peak of their cabins on the Salcha River and similar spots. The roosts are places where bats can rest in the daylight from their periods of hunting insects at dusk.

Following up on all the reports from people who have noticed bats in their buildings, biologists over the years have captured and tagged bats and have put out sound monitors to see when bats are squeaking around.

This delicate species’ association with manmade structures makes some biologists think bats exist in northern Alaska only because of us: our houses and sheds have made a marginal area to hibernate slightly more safe and warm.

But Reimer and other biologists recently found bat maternity colonies away from buildings. In the Copper River Valley, Reimer and her co-workers in summer 2017 radio-tagged mother bats at their cabin roost. When later tracking them with handheld receivers, they found the mother bats did not return to the cabin.

[content id=”79272″]

Instead, they tracked the bats to an old cottonwood tree that had a foot-high pile of bat guano at its base. They counted more than 100 bats flying out of a crack in the tree.

There was a natural bat nursery, which suggests to Reimer that little brown bats don’t need buildings, or humans, to thrive. Maybe they just roost in cabin crevices because they resemble the tight, dark spaces they rely upon in nature.

“Large maternity colonies in trees shoots down the theory that bats only came to Alaska as buildings went up,” she said.

As Reimer was making her discovery, Colorado State University scientists working on Fort Wainwright lands were finding the same thing. Sound detectors they installed in likely bat spots away from buildings picked up bat echolocation. Biologists radio-tracked bats to several dying or dead poplar and birch trees on Army lands near Fairbanks. They also tracked them to buildings.

One of those researchers, Garrett Savory, thinks their recent findings give a clue to one of the biggest mysteries surrounding far-northern bats:

“I think bats do hibernate in Interior Alaska, given that we have detected bats in early April, when there is still snow on the ground, and have detected bats late into September,” he said. “We still don’t know where bats hibernate, however.”

Reimer agrees that far-northern bats must be hibernating north of the Alaska Range, rather than migrating south through the mountains.

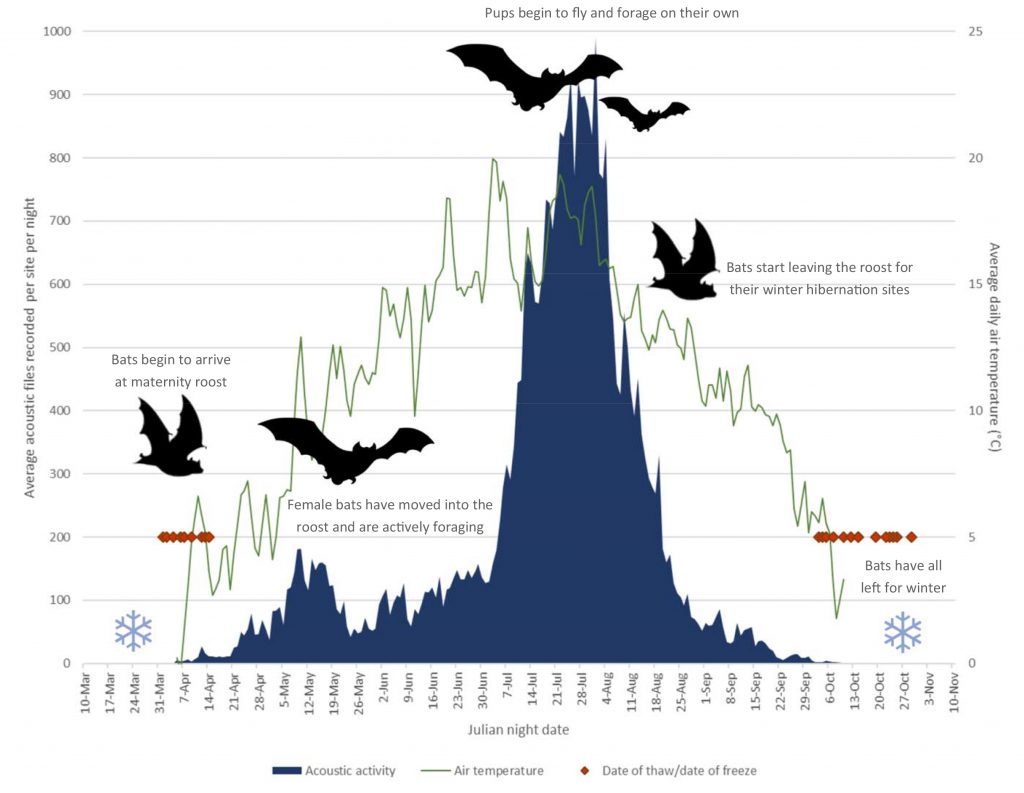

From the Kenai Peninsula to Fairbanks, in spring bats seem to all appear at their roost sites the instant the average air temperature gets above freezing. If they were migrating from farther south, there would probably be a time lag in the date the farthest-north bats arrived in Fairbanks compared to when they appeared on the Kenai.

“It seems to suggest that they are spending the winter nearby,” she said.

No one seems to know where those northern bats are right now. GPS transmitters are still not small enough to fit on a bat, Reimer said, and the radio tags biologists have used last only a week or two before they fall off.

Biologist Jesika Reimer of Taiga Wildlife Research in Anchorage created this graphic showing the summer activity of little brown bats in northern Alaska.

Scientists want to know the location of northern Alaska’s bats because white nose fungus has killed so many little brown bats in the Lower 48. Alaska bats have shown no sign of it yet, but the disease has reached Washington state after devastating bats in the eastern part of the country.

Reimer is now looking at genetic samples of Alaska little brown bats to compare them with farther-south populations.

“If they are meeting up (with Lower 48 bats) at some point, the likelihood of sharing the fungus is great,” she said.

But so far, so good. Alaska’s little brown bats may be saved from the disease because their adventurous ancestors chose extreme isolation.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.