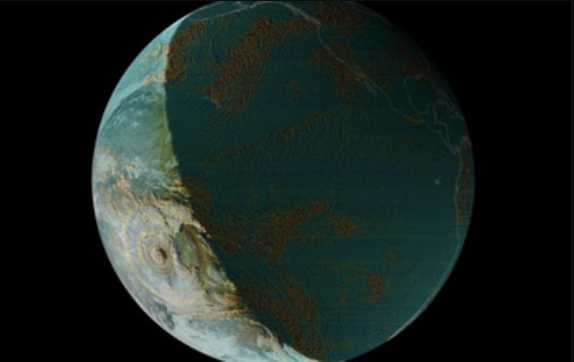

The massive Jan. 15, 2022, eruption of the Hunga submarine volcano in the South Pacific Ocean created a variety of atmospheric wave types, including booms heard 6,200 miles away in Alaska. It also created an atmospheric pulse that caused an unusual tsunami-like disturbance that arrived at Pacific shores sooner than the actual tsunami.

Those are among the many observations reported by a team of 76 scientists from 17 nations that researched the eruption’s atmospheric waves, the largest known from a volcano since the 1883 Krakatau eruption. The team’s work, compiled in an unusually short amount of time due to significant scientific interest in the eruption, was published today in the journal Science.

David Fee, director of the Wilson Alaska Technical Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, is a leading author of the research paper and among four of the center’s researchers involved in the work.

The Hunga eruption, near the island of Tonga, has provided unprecedented insight into the behavior of some atmospheric waves. A dense network of barometers, infrasound sensors and seismometers in Alaska — operated by the Geophysical Institute’s Wilson Alaska Technical Center, Alaska Volcano Observatory and Alaska Earthquake Center — contributed to the data.

“Our hope is that we will be better able to monitor volcanic eruptions and tsunamis by understanding the atmospheric waves from this eruption,” said Fee, who is also the coordinating scientist at the Geophysical Institute’s portion of the Alaska Volcano Observatory.

“The atmospheric waves were recorded globally across a wide frequency band, and by studying this remarkable dataset we will better understand acoustic and atmospheric wave generation, propagation and recording,” he said. “This has implications for monitoring nuclear explosions, volcanoes, earthquakes and a variety of other phenomena.”

The researchers found particularly interesting the behavior of the eruption’s Lamb wave, a type named for its 1917 discoverer, English mathematician Horace Lamb.

The largest atmospheric explosions, such as from volcanic eruptions and nuclear tests, create Lamb waves. They can last from minutes to several hours.

A Lamb wave is a type of guided wave, those that travel parallel along a material’s surface and also extend upward. With the Hunga eruption, the wave traveled along Earth’s surface and circled the planet in one direction four times and in the opposite direction three times — the same as observed in the 1883 Krakatau eruption.

“Lamb waves are rare. We have very few high-quality observations of them,” Fee said. “By understanding the Lamb wave, we can better understand the source and eruption. It is linked to the tsunami and volcanic plume generation and is also likely related to the higher-frequency infrasound and acoustic waves from the eruption.”

The Lamb wave consisted of at least two pulses near Hunga, with the first having a seven- to 10-minute pressure increase followed by a second and larger compression and subsequent long pressure decrease.

The wave also reached into Earth’s ionosphere, rising at 700 mph to an altitude of about 280 miles, according to data from ground-based stations.

A major difference with the Hunga explosion’s Lamb wave compared to the 1883 wave is the amount of data gathered due to more than a century of advancement in technology and a proliferation of sensors around the globe, according to the paper.

Scientists noted other findings about atmospheric waves associated with the eruption, including “remarkable” long-range infrasound — sounds too low in frequency to be heard by humans. Infrasound arrived after the Lamb wave and was followed by audible sounds in some regions.

Audible sounds, the paper notes, traveled about 6,200 miles to Alaska, where they were heard around the state as repeated booms about nine hours after the eruption.

“I heard the sounds but at the time definitely did not think it was from a volcanic eruption in the South Pacific,” Fee said.

The Alaska reports are the farthest documented accounts of audible sound from its source. That is due in part, the paper notes, to global population increases and advances in societal connectivity.

“We will be studying these signals for years to learn how the atmospheric waves were generated and how they propagated so well across Earth,” Fee said.

Other Geophysical Institute scientists involved in the research include graduate student Liam Toney, acoustic wave analysis, figure and animation production; postdoctoral researcher Alex Witsil, acoustic wave analysis and equivalent explosive yield analysis; and seismo-acoustic researcher Kenneth A. Macpherson, sensor response and data quality. All are with the Wilson Alaska Technical Center.

The Alaska Volcano Observatory, National Science Foundation and U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency funded the UAF portion of the research.

Robin S. Matoza of the University of California, Santa Barbara, is the paper’s lead author.