Findings highlight risk to whales and dolphins from vertical lines in marine environment.

A couple walking on the beach near Gustavus dock early on Sunday, May 30 were initially excited to spot a minke whale surface near a moored vessel. But then, they saw the whale dive and heard the mooring chain on the vessel pull taut, and the vessel spun around. That’s when they knew the whale was entangled.

A short time later, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve Whale Biologist Janet Neilson had received word of the entanglement at home. She reported it to NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Marine Mammal Stranding Hotline.

By the time Janet and her husband Sean, a photographer, arrived at the Gustavus dock, the whale had been seen repeatedly thrashing at the surface. It dragged the boat at least half a mile towards Pleasant Island. At that point, the thrashing stopped and Janet and others were hopeful the whale had been able to release itself from the entangling lines.

Janet scanned Icy Passage with binoculars while her husband launched his drone to search for the whale, but it was nowhere to be seen.

The vessel owner reported that he was able to recover all his gear, including the buoy, mooring line, 20–30 feet of chain, an anchor, and the engine block that served as a second anchor. He also found a small, thumbnail-sized piece of whale tissue stuck in the hardware on the mooring ball. The whale was free from the entanglement, but not without injury.

An Unhappy Ending

On June 1, a small dead whale was reported floating just west of the Gustavus dock in state waters. Janet and her co-worker Andrea Bendlin happened to be nearby on the Glacier Bay National Preserve (GBNP) whale research vessel Sand Lance and arrived at the carcass shortly afterward. They discovered that it was a female minke whale with external indications of entanglement.

“It was clear that this was the entangled whale from two days before. Minke whales are rare in our area and based on the timing, location, and injuries on the carcass, we quickly realized that this was the same whale,” said Janet Neilson. [content id=”79272″]

At NOAA Fisheries’ request, the U.S. Forest Service authorized the temporary landing of the whale in the intertidal zone on Pleasant Island, a designated wilderness area, for a necropsy.

NOAA Fisheries whale experts worked with the GBNP whale program lead Christine Gabriele to put together a team. Meanwhile, Janet and Andrea towed the carcass to shore for necropsy.

The Necropsy

A necropsy was performed on June 2 by GBNP personnel and volunteers. NOAA Fisheries veterinarian Kate Savage, who could not make it from Juneau to Gustavus due to weather, provided advice to the necropsy team by cell phone. A local whale watching boat also provided essential support.

Team members determined that the whale was a 26-foot-long adult female. They took numerous measurements, including blubber thickness, and collected samples of tissues, fluids, and parasites. Analysis of these samples will provide information about the health of the whale and the proximate causes of death.

Throughout the process, they looked internally and externally for the cause of death, including injury. They found a deep and ragged wound at the corner of the mouth, as well as abrasions under the left flipper and tail stock, indicating entanglement. Blood was also noted pouring from the blowhole during the necropsy, suggesting internal injuries.

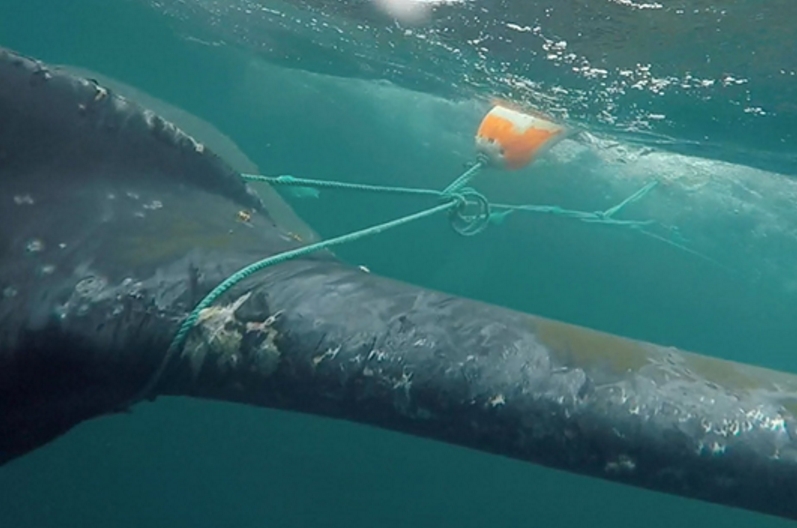

“Based on the necropsy findings and the account of the entanglement, including the tissue found on the mooring buoy, it is likely the line between the engine block and mooring buoy was caught in the whale’s mouth, with the mooring buoy tight to one side,” said NOAA’s Kate Savage. “The whale swam at least half a mile with the gear. She likely succumbed, either after self-releasing from the gear or becoming free of the gear after death. She then sank, and floated to the surface two days later.”

Savage says the whale probably died due to one of several possible scenarios:

- The engine block, chain, and anchor prevented the whale from surfacing; it consequently drowned.

- The entanglement caused injuries such as internal bleeding that led to its death. Capture myopathy, a syndrome associated with the capture and often overexertion of wild animals, may have also contributed to the mortality.

It is not clear how the unfortunate whale became entangled, but the mouth injury suggests it may have been feeding when it encountered the anchor line.

“Vertical lines in the water pose a significant risk to whales,” said Sadie Wright, large whale entanglement response coordinator with NOAA Fisheries Alaska Regional Office. “This is a good reminder that whenever possible, please remove lines from the marine environment when not in use.”

Following the necropsy, GBNP staff towed the whale carcass away from shore and released it later that evening—in keeping with the Forest Service wilderness designation.

NOAA Fisheries thanks our Alaska Marine Mammal Stranding Network partners at Glacier Bay National Park, as well as volunteers who assisted with the necropsy, and the U.S. Forest Service for authorizing the location for the necropsy.

For your own safety, and the safety of the animal, do not attempt to free an entangled marine mammal yourself. If you see a whale or marine mammal dead, entangled, or in distress, the best way to help is to report it immediately to the statewide, 24-hour stranding hotline at (877) 925-7773, or alert the U.S. Coast Guard on Channel 16.[content id=”79272″]