Waking to the smell of a wet ashtray (which, as a Child of the Seventies, I can still remember), I knew the wind had shifted. Wildfire smoke hung in the neighborhood.

This is not a reason for alarm: The nostalgic scent of vaporized spruce and willow trees is a normal summer sensation here in middle Alaska. But the 2023 Alaska wildfire season has been anything but normal, according to Rick Thoman.

Thoman is a climate specialist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy. He was also a meteorologist with the National Weather Service for decades before that. He remembers the specifics of random fire seasons in Alaska without looking down at a phone.

This summer has been a weird one, he said.

“There’s nothing like this,” Thoman said at his office on the University of Alaska Fairbanks campus recently. “Next to nothing through mid-July, then an explosion.”

First, a little background. We constructed much of peopled Alaska — especially Interior Alaska — in the boreal forest. The boreal forest is a swath of birch, aspen, spruce, willow and other trees that grow in enormous numbers from Alaska down through northern Canada all the way to the maritime provinces.

When that forest reaches maturity — in the form of 100-foot-tall white spruce or densely packed but much-smaller black spruce — it often renews itself by fire. Black spruce have tiny cones foresters call “serotinous,” which means they open when heated by fire. This enables the cones to shed seeds easier.

Fire most often erupts in Interior Alaska when lighting strikes dry trees or the ground. In arid and windy conditions, those flames quickly spread to other trees and tinder on the ground surface.

This June, while baseball games were canceled in Philadelphia and New York due to dense smoke from Canada’s burning boreal forest, we Alaskans barely sniffed a charred molecule.

By July 20, fewer than 2,000 acres of Alaska had burned. That’s about the footprint of the university campus in Fairbanks where I am now typing. That’s absurdly low for a state filthy rich in wildfire fuels, one in which patches that totaled more acreage than Vermont burned in 2004.

A persistent low-pressure system over the Bering Sea kept Southcentral and Southwest Alaska very wet in early summer 2023. The same system did not nurture thunderstorm conditions in Interior Alaska, Thoman said. Even though the middle of Alaska was very dry and trees were ripe to be burned, there was no ignition source.

Then, on a midsummer day, that stubborn weather pattern (which, like wildfire around the entire northern hemisphere this summer, is unrelated to El Nino, Thoman said) broke. Moisture, an important ingredient of lighting, entered Interior Alaska, along with warmth and a considerable temperature gradient through the air column.

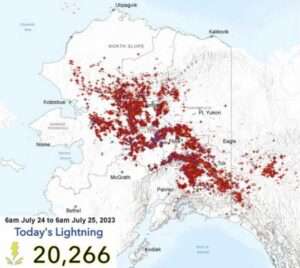

On July 24, automated systems recorded more than 20,000 lightning strikes over the face of Alaska and nearby areas in Canada.

“Most of the big fires ignited July 24, 25 and 26,” Thoman said. “Unlucky for us, all of the big fires are within 80 miles of Fairbanks.”

That means we have inhaled the tang of wildfire smoke on many days — but not all — since late July. Thoman said the smoke I tasted that morning was from forest burning near Anderson, to the southwest of Fairbanks. He determined this by knowing the low-level winds on that day were from the southwest.

Because of those recent, lightning-ignited fires, Alaska’s acreage burned has increased from the outline of the UAF campus to 290,000 acres on Aug. 17, 2023. That is less space than the municipality of Anchorage takes up.

The area of burned Alaska is less than half of Alaska’s yearly average to this point of the season.

Despite the fact that we are now experiencing cooler temperatures that come with less solar radiation as darkness returns, as well as higher humidity, Thoman is not yet ready to declare fire season 2023 a wrap.

“I wouldn’t call it over until we get a two-day rainstorm,” he said. “It will take an extinguishing rainstorm, or until the snow comes.”

[content id=”79272″]