The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) has revealed an extremely powerful magnetic field, beyond anything previously detected in the core of a galaxy, very close to the event horizon of a supermassive black hole.

This new observation helps astronomers to understand the structure and formation of these massive inhabitants of the centers of galaxies, and the twin high-speed jets of plasma they frequently eject from their poles. The results appear in the 17 April 2015 issue of the journal Science.

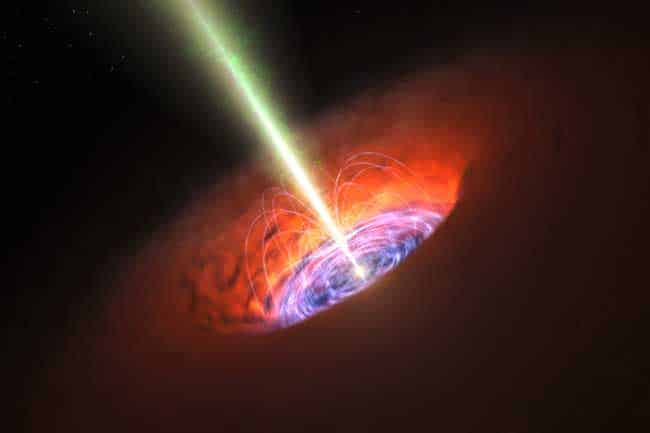

Supermassive black holes, often with masses billions of times that of the Sun, are located at the heart of almost all galaxies in the Universe. These black holes can accrete huge amounts of matter in the form of a surrounding disc. While most of this matter is fed into the black hole, some can escape moments before capture and be flung out into space at close to the speed of light as part of a jet of plasma. How this happens is not well understood, although it is thought that strong magnetic fields, acting very close to the event horizon, play a crucial part in this process, helping the matter to escape from the gaping jaws of darkness.

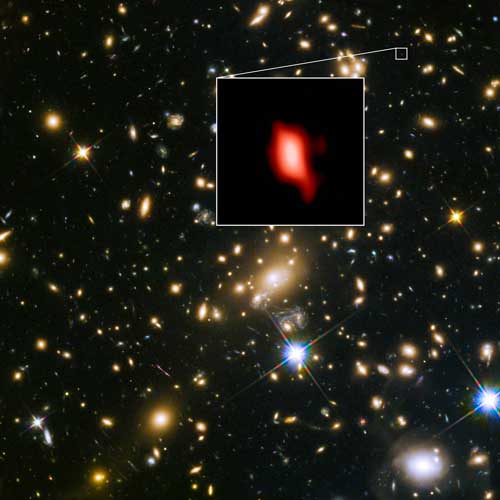

Up to now, only weak magnetic fields far from black holes — several light-years away — had been probed. In this study, however, astronomers from Chalmers University of Technology and Onsala Space Observatory in Sweden used ALMA to detect signals directly related to a strong magnetic field very close to the event horizon of the supermassive black hole in a distant galaxy named PKS 1830-211. This magnetic field is located precisely at the place where matter is suddenly boosted away from the black hole in the form of a jet.

The team measured the strength of the magnetic field by studying the way in which light was polarized as it moved away from the black hole.

“Polarization is an important property of light and is much used in daily life, for example in sun glasses or 3D glasses at the cinema,” says Ivan Marti-Vidal, lead author of this work. “When produced naturally, polarization can be used to measure magnetic fields, since light changes its polarization when it travels through a magnetized medium. In this case, the light that we detected with ALMA had been traveling through material very close to the black hole, a place full of highly magnetized plasma.”

The astronomers applied a new analysis technique that they had developed to the ALMA data and found that the direction of polarization of the radiation coming from the center of PKS 1830-211 had rotated. These are the shortest wavelengths ever used in this kind of study, which allow the regions very close to the central black hole to be probed.

“We have found clear signals of polarization rotation that are hundreds of times higher than the highest ever found in the Universe,” says Sebastien Muller, co-author of the paper. “Our discovery is a giant leap in terms of observing frequency, thanks to the use of ALMA, and in terms of distance to the black hole where the magnetic field has been probed — of the order of only a few light-days from the event horizon. These results, and future studies, will help us understand what is really going on in the immediate vicinity of supermassive black holes.”

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.