This new study looks at the timing and duration of the seaward migration from fresh to marine waters for juvenile coho, chum, and Chinook salmon.

Since 2014, NOAA Fisheries and Yukon Delta Fisheries Development Association scientists have been collecting data on young salmon. They want to better understand how environmental conditions affect them as they migrate out of the Yukon River. Changes in river discharge from winter ice melt and temperature may be influencing the timing and duration of juvenile chum, Chinook, and coho migrations.

However, the story on impacts is complex, varying by species. Scientists hope this new information will help answer a key question — as salmon migrations change due to shifting environmental conditions whether this leads to a mismatch with prey availability.

“This work is particularly important to help communities better understand what is behind the recent declines in salmon abundance across species and how natural and climate-induced environmental changes may alter migration patterns in the future,” said Katharine Miller, lead author of the new paper and fish biologist with Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

Unprecedented Salmon Declines Heighten Imperative for Research

Chinook salmon have been in a prolonged period of low productivity since the early 1990s. This resulted in a complete closure of commercial and subsistence fisheries in 2011 and 2020 respectively. Chum and coho salmon suffered catastrophic declines in adult returns beginning in 2021 and have been closed to commercial and subsistence fishing since.

High latitude rivers, like the Yukon River, are warming at a rate nearly twice as rapid as more temperate areas.

“Salmon is the lifeblood for Indigenous peoples who have made their home along the Yukon River for thousands of years. People rely heavily on land and water subsistence resources to feed their families due to a lack of grocery stores and the availability of affordable high-quality food. Besides serving as a critical food source, salmon also play a significant role in the region’s culture, traditions, and economy,” said Courtney Weiss, co-author of the new paper and research scientist with the Yukon Delta Fisheries Development Association.

Seasonal Timing of Salmon Life Cycle Events

Migration from freshwater to the ocean is a critical time in the development of juvenile salmon. During this time, salmon undergo a lot of changes, including:

- Physical changes in how they look (e.g., size and shape)

- Functional and behavioral changes

- The rate at which these changes happen in response to environmental cues and river conditions

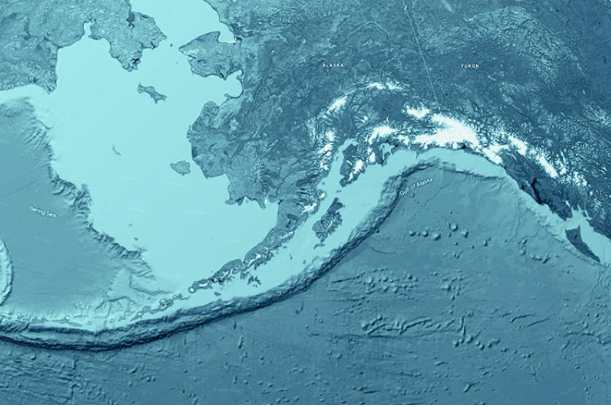

The Yukon River, located in northwest Canada and central Alaska, is the fourth largest river in North America. It is one of its largest and most diverse intact ecosystems. Juvenile salmon traversing the Yukon have some of the longest downstream migrations in the world. Some salmon travel as far as 1,800 miles from freshwater in Canada before entering the Bering Sea. Once in the ocean, some salmon spend several years before returning to start the cycle again.

For salmon, survival of juvenile fish is higher when river outmigration coincides with optimal ocean prey and environmental conditions.

“Migration distributions contain a wealth of information on how salmon respond to environmental variability and potentially climate change,” said Miller

River Discharge and Temperature Influences on Salmon Migration

Scientists considered two factors influencing salmon migration and timing for the three species in the Yukon River:

- Influence of river flow

- To a limited degree, temperature data (air temperature data was used as a proxy for water temperature)

Between 2014-2019 and 2021, scientists measured and released more than 75,000 juvenile salmon at nine permanent stations on the three main tributaries of the lower Yukon River. More than 91 percent of these fish were juvenile chum salmon, 5.1 percent were Chinook, and 3.4 percent were coho.

Juvenile Chinook salmon had the most variability in migration timing and duration of the three species. Their migration was most closely correlated with the maximum river discharge, which occurred in June.

Scientists suspect that discharge had less of an effect on coho because they spend between 1–3 years of their freshwater juvenile stage in low-velocity pools and off-channel habitats. They also have the shortest migration duration.

July air temperatures appeared to affect Chinook and chum salmon outmigration differently. Scientists found that for Chinook, maximum July temperatures resulted in more variability in the timing of migration and shorter migration durations. For chum, their migration duration also decreased, but there was less variability in the migration timing among fish. Fish distribution during the migration was also more concentrated.

The story is complicated by the genetic composition of Chinook and chum salmon stocks. Chinook have 36 spatially distinct populations that migrate together. However, the proportional contribution of the individual populations changes during the migration period. Chum salmon have different fall and summer populations. The various populations of Chinook and chum are likely sensitive to local environmental factors because they come from different locations all along the river.

Seasonally migratory species, such as salmon, can adjust their migration timing in response to altered discharge and temperatures. However, changes in migration timing may result in mismatches between the migrants and suitable ocean conditions or prey availability.

“Now that we have a better idea of when environmental factors are most important to migration processes, we are going to be evaluating what that means in terms of prey overlap and ocean conditions at the time of marine entry. This is really just the beginning of important work that needs to be done,” said Miller.

Some future research needed includes:

- Systematic collection of water temperature data in the Yukon River Basin

- Further studies to better understand the influence of water temperature and the environmental complexities across populations that are likely influencing migration variability

- Additional studies to identify critical links to marine survival and adult returns

NOAA-Alaska Fisheries Science Center

[content id=”79272″]