A chemical signature recorded on the ear bones of Chinook salmon from Alaska’s Bristol Bay region could tell scientists and resource managers where they are born and how they spend their first year of life.

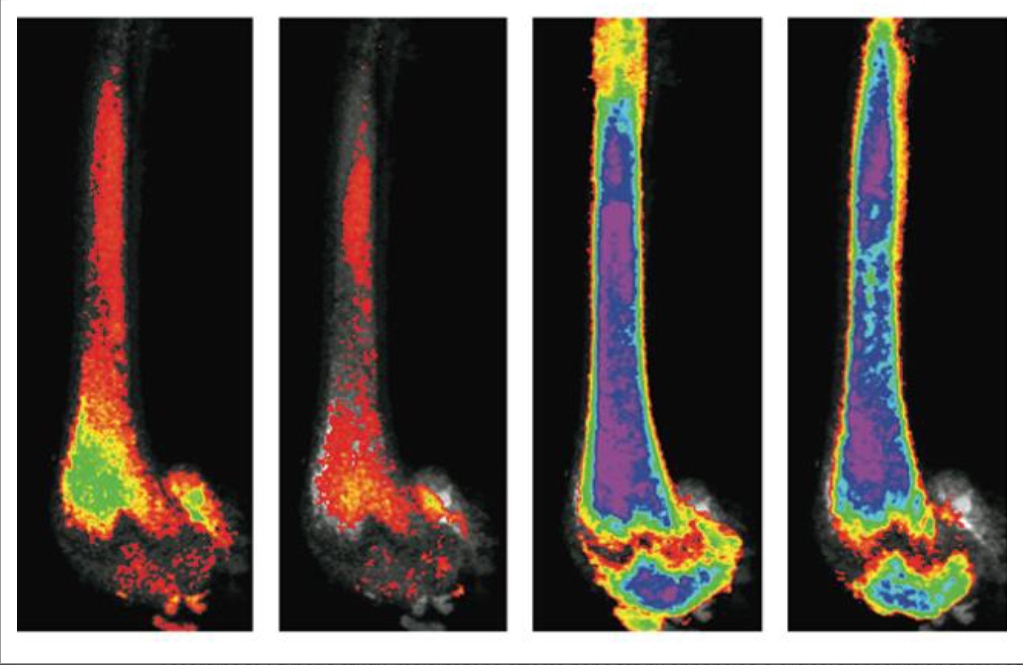

This bone, called an otolith, accumulates layers as a fish grows, similar to trees. These “growth rings” are produced throughout a salmon’s life. Scientists can tell where the fish lived by matching the chemical signatures of the otolith with the chemical signatures of the water in which they swim, according to astudy published May 15 in the online, open-access journalScience Advances.

“Each fish has this little recorder, and we can reveal the whole life history of the fish from the perspective of the otolith. Each growth ring is a direct reflection of the environment the fish was swimming in at the time it was formed,” said lead author Sean Brennan, who completed the study as a doctoral student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He is now a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences.

This chemical signature comes from isotopes of the trace element strontium, found in bedrock. Strontium’s chemical makeup varies geographically. As rushing water weathers the rocks, the element is dissolved and released into the water. The dissolved strontium ions get picked up by fish, either through the gills or gut lining, then are deposited onto the otolith.

As strontium makes its way from rocks into the otoliths of fish swimming in the rivers, its chemical signature does not change, and so it serves as a robust tag that can tie each fish as being in a specific location in the river at a specific time.

“This particular element and its isotopes are very strongly related to geography,” said Matthew Wooller, director of the Alaska Stable Isotope Facility at University of Alaska Fairbanks and a co-author of the paper. “It is a really good marker for where animals have been and whether they move around in their environment.”

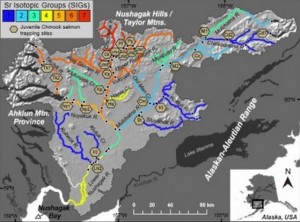

This process relies on a river system that has been mapped extensively for its strontium isotope variation. In general, watersheds that are diverse in the types and ages of rocks will also have a lot of variation in strontium isotope signatures – and thus are good candidates for using this technique, Brennan said.

“Alaska is a mosaic of geologic heterogeneity,” he added. “As long as you can look at a geologic map and see rocks that are really different, that’s a good potential area.”

The Bristol Bay region in Alaska produces some of the last remaining wild salmon runs in the world. The area is perhaps best known for its sockeye salmon commercial fishery, but Chinook salmon, particularly those in theNushagak River where this study took place, supply important subsistence and sport fisheries for the region. The Nushagak Chinook salmon are also the third biggest run in Western Alaska, ranking it as one of the largest worldwide.

About 200,000 Chinook make their way each summer from the ocean to spawn in the river’s upper tributaries and streams. When their eggs hatch in the spring, young Chinook salmon spend a whole year in the river, feeding and growing before migrating to the Bering Sea and the Pacific Ocean.

Pages: 1 2