The pollock fishery in the Gulf of Alaska is unique in many ways. The pollock fishery in Alaska’s Bering Sea is rationalized, which means each vessel/permit holder is allocated a certain amount of catch for the season. But the Gulf of Alaska pollock fishery is open access, with every vessel racing against the others for catch.

The pollock fleet also fishes in the waters where Chinook salmon feed before returning to inland rivers to spawn. Traditionally, vessels must discard 100 percent of the Chinook and other prohibited species incidentally caught—known as bycatch. The goal is to minimize impacts to these commercially and culturally valuable species. The pollock fishery has a very low rate of bycatch (less than 1 percent). Additionally, there is a cap on Chinook bycatch. When it’s met, the fishery for pollock is closed.

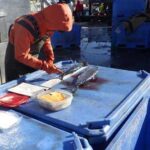

Kiley Thompson knows the fishery well. He has been fishing in Alaska waters for nearly 30 years. After getting a job in college fishing for salmon, it eventually became his full-time profession. Today, he fishes along with three crew members in the Gulf of Alaska pollock fishery on the F/V Decision, a 58-foot seiner/trawler based in Sand Point, Alaska.

Traditionally, fisheries observers were randomly assigned to 20 to 30 percent of the trawler fishing trips to collect data on catch. This ensured reliable estimates of salmon bycatch. However, the fishing ports are rural—for instance, Sand Point is about 600 miles southwest of Anchorage, and only accessible by air or boat. It can be difficult to guarantee observer availability, with weather conditions routinely delaying flights by hours or several days. “The biggest challenge for us is getting observers, and you can end up losing fishing time” waiting for them to arrive, Thompson says.

Turning to Electronic Monitoring

In the face of these challenges, the Gulf of Alaska fleet turned to emerging electronic monitoring technologies. In 2019, the fleet and other trawl organizations across the state piloted EM systems. They ran side by side with observers for the first year and then continued under an exempted fishing permit beginning in 2020.

With these systems, cameras are installed to offer a view of the entire deck, and all Chinook or other prohibited species are retained by the boat. The video is collected on a hard drive that is mailed to third-party video reviewers for analysis to ensure there were no unauthorized discards at sea. Meanwhile, a shoreside observer monitors offloading at the pier and is able to collect information on the landings and biological data. The observer data and video reviewer’s information are transmitted to NOAA Fisheries. The two components complete a full picture of the fishing trip.

There have been some growing pains with the program. Some fishermen are uncomfortable with the 24/7 nature of the cameras. The cameras also require maintenance given the harsh weather conditions in which they operate. But the challenges of getting a technician or replacement part for self-service to the fishing port aren’t any more difficult than those of making sure an observer is available. At Sand Point and nearby King Cove, nearly all the pollock trawl fleet is now covered through EM systems. The handful that have not yet adopted the technologies are slated to do so soon.

The 100 percent camera coverage comes with several advantages. It gives greater confidence in the ongoing count against the cap on Chinook bycatch. With traditional observer coverage, if one observed trip happens to have a lot of bycatch, it contributes to the extrapolation of information applied to the unobserved trips. However, with the camera system, all catch goes to shore, where shoreside observers can collect down-to-the-fish counts of bycatch.

It also allows for greater accountability within the fleet. “We can avoid hotspots because we have real-time data,” says Thompson. In fact, the fleet has begun compiling a collaborative data portal in conjunction with the EM program and fish ticket data. “Why not put all the data we have in logbooks—bycatch, target, location—and make it public so we can use it to avoid bycatch?” asks Thompson.

“It’s still in its infancy, but it’s working well so far. I can look on my phone to see where bycatch has happened—though not total pounds—and we can make real-time decisions as we leave the dock. Am I going left or right, and how can I adjust the depth of gear to avoid bycatch?” he continues. “It’s truly showing what’s been caught, and we haven’t had a closure since we started piloting the data portal.”

Looking Ahead

In the coming years, Thompson sees an even greater role for technology. This could include sensors on gear that can automatically communicate when it is set, its location, depth, and other information. He also envisions the data portal growing beyond a cooperative effort within the fleet to a larger collaboration with EM vendors and NOAA Fisheries. This could make the data even more timely and effective in avoiding bycatch or low-yield target trips. “I could realize that the three boats who went out in front of me had bad trips so I should pull in rather than continuing to fish,” he predicts.

“For small Alaska ports, electronic monitoring makes so much sense,” Thompson says. EM systems “never have a delayed flight,” and, coupled with the data portal, allow fishermen to more thoroughly account for bycatch and target their fishing operations more nimbly. “If we catch less Chinook, we can catch more pollock.”

[content id=”79272″]