Scientists in northern Alaska are learning about polar bears by scraping snow samples from the tracks they leave behind.

That snow contains tiny flecks of the massive creatures — mostly cells shed from their foot pads. From the DNA within those cells, scientists have been able to identify individual polar bears.

Lisette Waits of the University of Idaho was in Fairbanks recently at an Alaska Chapter of the Wildlife Society meeting to talk about a wildlife-sampling method that does not include a helicopter, dart gun or handling of a drugged polar bear that can weigh as much as four NFL linemen.

In her genetics lab in Moscow, Idaho, Waits and her colleagues have processed melted snow skimmed from polar bear tracks in Utqiaġvik, Wainwright and Kaktovik. That broth includes some cells that have allowed scientists to get a DNA fingerprint of a particular polar bear.

Scientists want to find out more about an animal dependent on northern sea ice, a substance that has been steadily decreasing for as long as we’ve had a good look at it. Polar bears use sea ice as a platform for hunting ringed seals, the fatty staple of their diets.

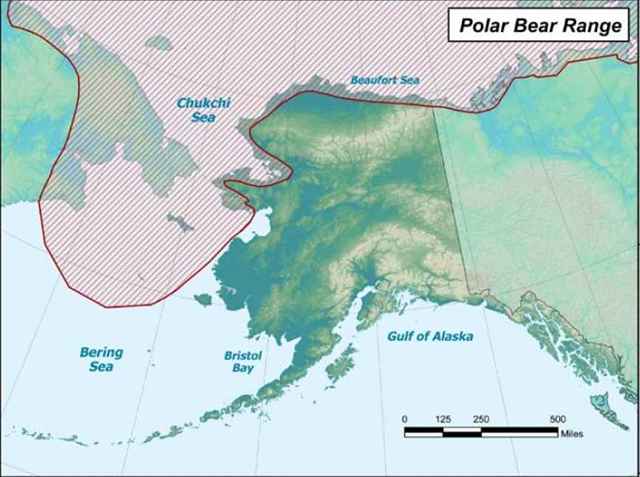

Polar bears of the northern sea ice number from about 20,000 to 30,000 animals, with the waters and shorelines of northern and western Alaska supporting an unknown number. Scientists have identified two populations of polar bears in Alaska: a Chukchi Sea group that also expands to Russia and Beaufort Sea animals that extend into northern Canada.

Scientists want to know more about the numbers of these iconic carnivores, which are coping with a warming climate that is greatly affecting their ephemeral hunting grounds.

“With less sea ice, the bears have to spend more time on land,” Waits said.

More time on land may subject polar bears to more competition for food from brown bears and other animals.

For the past several years, a team including biologists with the North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management in Utqiaġvik and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game has experimented with using sterilized trowels to scrape a thin layer of snow from fresh polar bear footprints.

Waits, who has studied Galapagos bats, red pandas in Nepal and bears of the Andes, showed at her presentation that about half of those polar-bear track samples yielded viable nuclear DNA. Nuclear DNA allows scientists not only to say that those molecules came from a polar bear, but also which specific bear left the track.

While the technique is still at an experimental stage with more work required before it becomes a reliable tool, longtime Utqiaġvik resident and retired biologist Craig George said the potential of the DNA-from-bear-tracks method impresses him.

“To think that a polar bear walking across the sea ice leaves enough DNA in its footprint to identify and genotype a bear is astonishing,” he said in an email.

[content id=”79272″]