Researchers seeking potential replacements for current antibiotics losing their effectiveness against multidrug-resistant pathogens have identified a possible option in the protective mucus that coats young fish.

The team, led by principal investigator Sandra Loesgen at Oregon State University, presented their findings at the recent meeting of the American Chemical Society Spring 2019 National meeting and Exposition in Orlando, Florida.

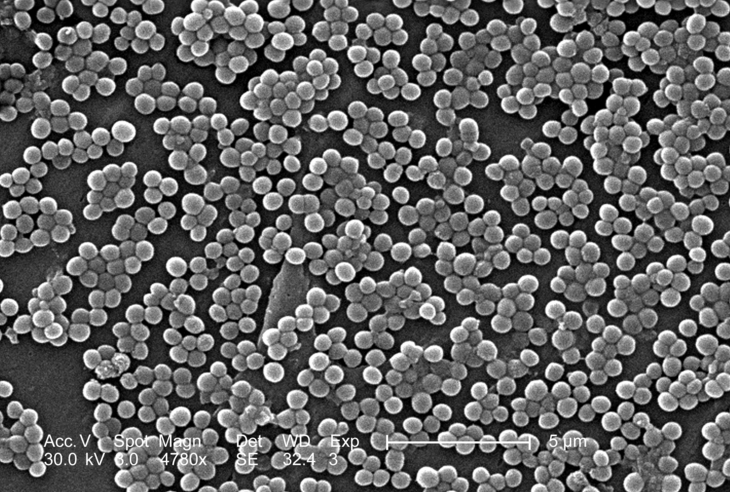

The bacteria is seen as a promising antibiotic to counter known pathogens, even dangerous organisms such as the microbe that causes MRSA infections. MRSA, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, is a bacterium that causes infections in different parts of the body and is resistant to come commonly used antibiotics.

The protective mucus coating young fish is a viscous substance that protects fish from bacteria, fungi and viruses in their environment, trapping the microbes before they can cause infections.

The slime is also rich in polysaccharides and peptides known to have antibacterial activity.

[content id=”79272″]

According to Molly Austin, an undergraduate chemistry student in Loesgen’s laboratory, the fish mucus is interesting because the environment the fish live in is complex. “They are in contact with their environment all the time with many pathogenic viruses,” she said.

Others on the team supplied mucus swabbed from juvenile deep-sea and surface-dwelling fish caught off the Southern California coast, and screened 47 different strains of bacteria from the slime. Five bacterial extracts strongly inhibited methicillin-resistant MRSA and three inhibited Candida albicans, a fungus pathogenic to humans. A bacteria from mucus from a particular Pacific pink perch showed strong activity against MRSA and against a colon carcinoma cell line.

While the research team is interested in new sources for antibiotics to help people, they are also looking at other ways to apply this knowledge. For example, they said, the study of fish mucus could help reduce the use of antibiotics in fish farming by leading to better antibiotics specifically targeted to the microbes clinging to certain types of fish.

But first, Loesgen said, they want to understand more fundamental questions, such as what makes healthy microbiomes, which are microorganisms in a particular environment, including the human body. Their research was reported by EurekAlert, the online journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Fishermen’s News Online grants permission to the Alaska Native News to post selected articles. Read More at: Fishermen’s News Online.