MISHAWAKA, INDIANA — The saws, the sanding, the hammering. The constant sounds of construction are music to the ears of country music star Garth Brooks.

“That sound you are hearing right there, that’s love,” he said, competing to have his voice heard over the ever-increasing buzz of activity that surrounds him on this construction site.

For Ericka Santiestepan, a single mother of two young children, the slam of a hammer hitting a nail is also the sound of hope.

“I feel like I won the lotto. It’s means everything. I don’t have to worry about where I’m going to have to go next,” she told VOA.

That’s because when the A-frame trusses Brooks is helping build are finally raised, they form the roof over Santiestepan’s new, permanent home.

“I’m in a house,” she said, grinning, “and I have these amazing people to help me — Garth Brooks and Trisha (Yearwood) are working on my house. I want them to sign the inside of my walls!”

Hand up, not a hand out

Santiestepan isn’t getting anything for free. Once the house is built, she will have a mortgage, albeit an affordable one, thanks to Habitat for Humanity’s no-interest loan, paid for by Santiestepan’s own “sweat equity” during this construction project.

“It’s a hand up, not a hand out,” country music star Yearwood explained. She and husband, Brooks, are just two volunteers among hundreds in what is a massive volunteer effort on the outskirts of South Bend, Indiana, to build nearly two dozen homes similar to and alongside Santiestepan’s.

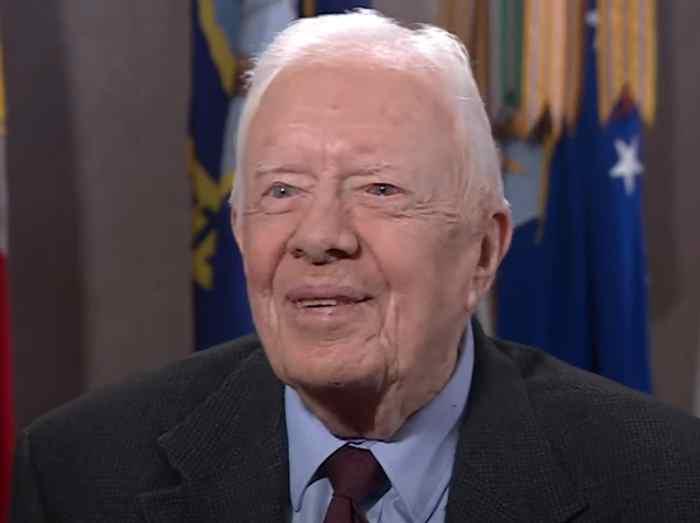

This newly forming neighborhood is the current focus of Habitat for Humanity’s Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Work Project, an annual event the former president and first lady began in 1984.

“The myth is that President and Mrs. Carter started Habitat,” said Jonathan Reckford, Habitat for Humanity’s chief executive officer. The nonprofit organization was in fact founded in 1976 by Millard and Linda Fuller.

The headquarters is in Americus, Georgia, not far from Carter’s hometown of Plains. After some cajoling, the Fullers encouraged the Carters, who returned to Plains in 1981 after a stinging electoral defeat to Ronald Reagan, to participate in a local build project in 1984. Thirty-four years later, they continue to lend their name and muscle to Habitat’s global effort to build homes for those in need.

“I think every human being would probably like some excitement in their life, some challenge in their life, some particular thing for which they can be grateful in the future, some obstacle to overcome, something from which they could be proud. And Habitat answers all those questions for me,” Carter explained during a news conference on this year’s construction site.

One week work project

Though the house-building project takes place for one week a year, the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Habitat for Humanity Work Project is now one of the most identifiable aspects of their legacy.

“When the Carters got involved, worldwide, lifetime to date, Habitat had helped 758 families,” Reckford said. “Since they got involved, we’ve been able to partner with 13.2 million people to have new, rehabbed, or repaired homes. And right now, we are at a pace that we are partnering with someone in the world every 50 seconds. And there is really no one that has had more to do with that than President and Mrs. Carter.”

Intense heat, advanced age and even cancer have not kept the Carters from building houses across the United States and 14 other countries, working alongside volunteers like Suzanne Taylor.

“He said once that he’s going to do as much as he can with as much as he can for as long as he can because his faith demands it,” Taylor said. “I think it’s a lesson to all of us to maybe get off the couch a couple more times and go do something to make the world a better place.”

“Nobody works harder than them, and they set an example for everybody. They really do,” Yearwood said, standing near the former president and first lady as they cut wood and assembled material that will eventually become a front porch railing.

Gratitude is motivating

Brooks admits that although he is 38 years younger than Jimmy Carter, volunteering alongside him is an exercise in intimidation.

“You don’t keep up with him. You are just scared not to,” Brooks said half-joking, smiling. “He just puts the fear of God into you. He says it’s not a race, as long as his house is done first.”

It’s a race that Santiestepan, whose future home stands next to the one Jimmy Carter was building the railing for, is happy to lose.

She didn’t know anything about the Carters before the project began, and now doesn’t need to do a Google search to learn more. She’ll be living in a community built in part by their compassion.

“Every time I think about it, I just want to cry, just because without them, I couldn’t do it,” Santiestepan said, fighting back tears. “I wouldn’t have this. I wouldn’t know where I would be next year. I’m grateful from the bottom of my heart. It just means a lot. They have no idea what they are doing for everyone. I mean, they know, but I don’t know if they can feel exactly how it feels like. It’s a dream come true.”

The gratitude shown by new homeowners like Santiestepan is one highly motivating factor that keeps the Carters returning to construction sites year after year.

“Just to see the expression on their face,” the former president said, fighting back his own tears. “They start crying first, and I start crying right behind them, and it’s a matter of deep emotion for me. And I’m already emotional about this project, as you can tell.”

It’s a project that when completed will put 23 modern homes on Mishawaka’s map this year, joining more than 4,000 on the global map since 1984. And all built by a former president who grew up in a house with no running water or electricity.

Kane Farabaugh is the Midwest Correspondent for Voice of America, where since 2008 he has established Voice of America’s presence in the heartland of America.

Source: VOA