(Vancouver, B.C.) — Two years after the B.C. Auditor General called for sweeping reforms to mine compliance, enforcement and reclamation bonding, the B.C. government is quietly soliciting comments on watered-down reclamation security policy recommendations with little outreach and a tight deadline of November 8. There are numerous deeply informed reports calling for clear changes, so communities in B.C., as well as in the downstream bordering states of Alaska and Montana, are concerned this move is a masked exercise in maintaining the status quo.

The Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources (MEMPR) is revising its mine reclamation security policy using a solicited Ernst & Young report from last year. The report’s recommendations don’t address key problems identified by the Auditor General:

B.C. taxpayers —not mining companies — are on the hook for catastrophic failures at mines, just as they were for the 2014 Mount Polley mine disaster.

B.C. does not ensure that mine water treatment long into the future is paid for by mine owners. Acid and toxic pollution can flow from mining waste for centuries, either leaving B.C. watersheds polluted or B.C. taxpayers paying for clean-up.

There is very little transparency in the reclamation bonding estimation process. Consultants hired by the mining company — or the mining company itself — estimate the cost of reclamation with the B.C. government behind closed doors.

B.C. only requires that mine companies post a partial reclamation security before mine operations can begin, and B.C. gives mining companies plenty of easy ways to reduce their reclamation bond requirements. Thus, B.C. taxpayers are on the hook, across the province, for $1.6 billion in mine pollution cleanup.

In southeastern B.C.’s Elk Valley, where Teck Resource’s huge mountaintop-removal coal mines are responsible for most of Teck’s reclamation bonding shortfall of more than $1 billion in B.C., toxic mine waste is expected to flow downstream in B.C. and Montana for many centuries. Teck owns more mines in total than any other company in the province and has been required to put up more money towards the reclamation of its one Alaska mine, Red Dog, than all thirteen of its B.C. mines combined.

“Reclamation bonding in the Elk Valley is a black hole,” says Lars Sander-Green from local conservation group Wildsight. “Teck doesn’t have a long-term solution to their water pollution problem and no one outside of government can even read their reclamation cost estimate. We know there won’t be enough to pay for expensive water treatment for centuries.”

[content id=”79272″]

In the Elk Valley, the policy shortcomings listed above mean B.C. taxpayers are at risk of holding the bag for billions of dollars in water treatment costs over many centuries.

Robyn Allan, a B.C. economist who has written mining reports on the implementation of the polluter pays principle in B.C, clearly stated in “Canadian Mines on Transboundary Rivers”— a report she prepared for a concerned Alaska State Legislature — that a robust polluter pays regime incentivizes companies to adopt best practices and release less hazardous waste, which results in fewer accidents and fewer bankruptcies.

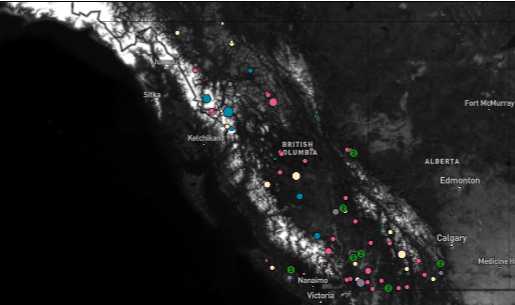

According to Heather Hardcastle, advisor at Salmon Beyond Borders, “With at least 12 new open pit Canadian mines in various stages of permitting, construction, and operation near the headwaters of three major transboundary salmon rivers that flow from B.C. into Alaska, and B.C.’s dismal past record of holding mining companies accountable for their pollution, B.C.’s inadequate reclamation bonding policy is a nightmare scenario for downstream communities, jobs, and fish.”

British Columbia’s NDP government won the election on a strong environmental platform. Where the mining sector is concerned, however, it is continuing the practice of corporate-led “reforms” that offer no real substance, leave B.C. taxpayers vulnerable, and may well affect B.C. and U.S. downstream communities, as well as environmentally-based resources like fisheries and tourism, for generations to come.