Quiet enough to hear a pin drop or so noisy you can barely hear the person next to you? NOAA is now undertaking a novel effort to answer these questions.

In 2014 NOAA began establishing its first-ever coordinated Ocean Noise Reference Station Network—a set of 10 undersea listening stations deployed around the United States designed to systematically measure ambient noise levels in the ocean. This effort—led by the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in collaboration with NOAA Fisheries, NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuaries, and the National Park Service—represents the first large-scale effort to monitor long-term changes and trends in underwater sound spanning vast swaths of U.S. waters. The ocean noise network will “help scientists understand what ambient ocean sound levels are now, how they are changing over time, and what impacts man-made noise could have on marine life,” explains Principal Investigator Holger Klinck from NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

The Significance of Background Noise to Marine Life

One of the biggest concerns with ocean background noise is the potential for an undersea version of the “cocktail party effect”—an inability for species to hear each other in a noisy ocean environment. This concern is significant because many marine animals depend on sound for their most basic needs—food, communication, protection, reproduction, and navigation. Toothed whales, like sperm whales, use sound to find and identify prey sources like squid and use sound to navigate and communicate with their family groups. Many baleen whales—like humpback, blue, and fin whales—regularly repeat their songs for long-distance communication, and likely even for reproduction. And the importance of sound isn’t limited to marine mammals, but extends to fish and invertebrates as well. Caribbean spiny lobsters make raspy sounds to help them escape predatory octopuses. Oyster toadfish produce sounds to attract females. Tropical coral larvae may even use sound to detect ideal reef habitats.

Could background noise really be significant enough to affect marine life? Initial research suggests the answer to this question is yes. An August 2012 article in the journal Conservation Biology showed that background noise from ships significantly reduced the ability of endangered North Atlantic right whales to communicate.

Another article, published in Biology Letters, showed that blue whales changed their calling behavior in response to relatively low source level seismic survey sounds, calling more during periods without seismic noise. Creation of the NOAA ocean noise network is particularly timely given the impending creation of new shipping lanes in the Arctic, the opening of the widened Panama Canal, and the subsequent changes in background noise levels for marine life these new traffic patterns could engender. “Being able to produce and detect sound is critically important to many marine species, so changes to the natural background soundscape may have more effects on ecosystem health than previously thought,” explained NOAA Fisheries Biologist Jason Gedamke, one of the project leaders.

Trends in Underwater Ambient Noise | What We Know So Far

The new NOAA ocean noise network will provide data on baseline ambient noise levels in U.S. waters and fill critical information gaps, as current information on trends in ambient ocean noise is limited. Looking at what type of information currently exists, one study shows that ocean ambient noise increased in the Northeast Pacific (west of San Nicolas Island, California) over a period of more than 40 years. The cause is attributed to increases in commercial shipping. Another study shows variability in recent trends of ship traffic noise, which has been increasing at some locations and decreasing or remaining the same at others. But despite the collection of underwater sound information by the scientific community, the military, and other sources, information is still lacking on background ocean sound levels and how they might be changing over long time frames.

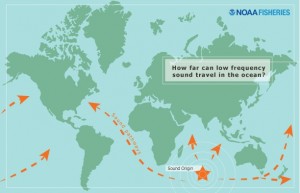

If sound is increasing, it may be in part because it travels so far, leaving few places for marine life to escape it and making it that much more important to measure. Lower frequency sound can travel thousands of miles. An experiment conducted in the early 1990s showed that sound emitted from Heard Island (near Australia as shown in the diagram above) was picked up at sites in the Northern and Southern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans as well as the Indian and Southern Oceans.

Sound from seismic airguns was also recorded from more than 4,000 km (2,500 miles) away—that’s almost the distance of the entire Pacific Crest Trail that goes from Mexico to Canada. This means that it’s not just the underwater noise produced locally that matters; noise occurring around the world’s oceans could be affecting ambient ocean sound conditions both near and far.