For more than two decades, Alaska has led the way in using ecosystem information to inform resource management decisions. In 2020, contributions from research partners and local communities together with NOAA scientists helped fill some data gaps.

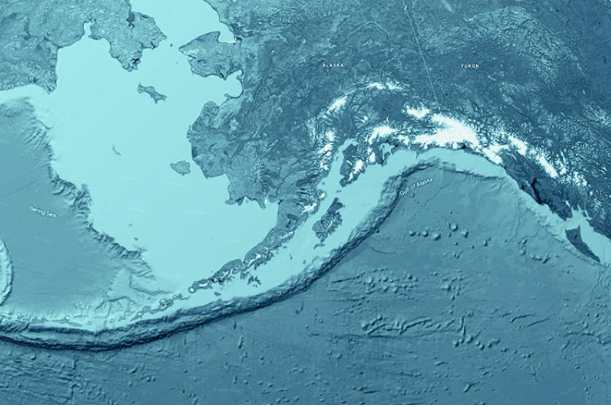

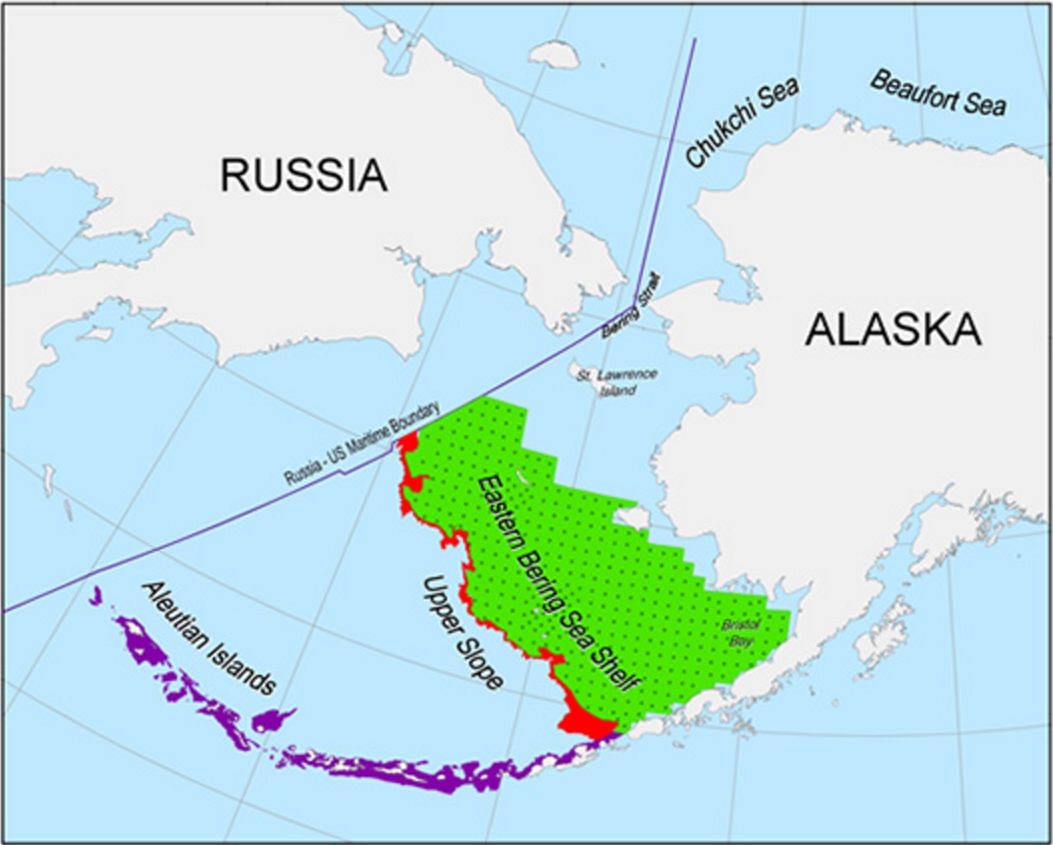

Each year, NOAA Fisheries scientists compile information from a variety of sources to produce and update annual indicators of ecosystem status in the Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian Islands. Data and information are provided by federal, state, academic, non-government organizations, private companies, and local community partners across Alaska. Collected data complement NOAA Fisheries’ own research.

Each year, NOAA Fisheries scientists compile information from a variety of sources to produce and update annual indicators of ecosystem status in the Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian Islands. Data and information are provided by federal, state, academic, non-government organizations, private companies, and local community partners across Alaska. Collected data complement NOAA Fisheries’ own research.

However, in 2020 several key NOAA research surveys were cancelled. Collaboration, increased engagement by community and research partners, and creative thinking on the part of some NOAA scientists helped fill critical information gaps. As a result, the annual Ecosystem Status Reports still could be produced.

“Around 143 individuals contributed to the three Ecosystem Status Reports we produced this year,” said Elizabeth Sidden, editor of the Eastern Bering Sea Ecosystem Status Report and a scientist at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “The success of this continuing effort to provide valuable ecosystem context to better understand factors contributing to fish stock fluctuations hinges on these partnerships. We couldn’t do this without the help of fellow researchers and local communities along with our staff contributions.”

One example of the kind of information provided by partners this year in all regions is seabird data. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (U.S. FWS) was unable to conduct field research due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. Coastal community members, tribal governments, and state and university partners provided information on seabird dynamics for the Bering Sea region. U.S. FWS biologists then synthesized that data. In the Gulf of Alaska, they provided opportunistic observations that were incorporated into the Ecosystem Status Report along with other information from non-profits, The Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team (COASST) and U.S. Geological Survey. Seabird biology and ecology are bellwethers of environmental change, which is one of the reasons they are important ecosystem indicators.

NOAA scientists also identified other sources of information to develop ecosystem indicators in 2020. For instance, they used satellite data to measure sea surface temperatures in the Bering Sea since they weren’t able to collect these data during annual research surveys. They also were able to process and analyze data collected from previous years of surveys.

Ecosystem Indicators Help Us Understand Health of Fish Stocks and Human Communities

Fish, crabs, and other marine life are integrally connected to their environment. Changes in environmental conditions such as water temperature, ocean currents, food availability, and predation affect species at different stages throughout their lives. Effects may include changes in their reproduction, growth, development, and survival. Thus, monitoring and understanding environmental changes is important.

When environmental conditions vary so does human behavior including fishing activity and effort. For example, when fish move to areas where environmental conditions are more favorable, fishing vessels are likely to follow. This was the case in recent years when commercial long-line and pot fishing vessels shifted farther north in the Bering Sea to catch Pacific cod. The cod had moved northward due to the loss of the natural barrier created by annual sea ice melt, the cold pool, and warmer ocean temperatures.

“In evaluating the status of the ecosystem, it is also important that we look at how the communities and businesses who are dependent on marine resources are affected by changing environmental conditions,” said Bridget Ferriss, editor of the Gulf of Alaska Ecosystem Status Report and a scientist at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “We also look at human indicators such as school enrollment to gauge the well-being of local communities.”

Ecosystem Data Use in 2021 Fish Stock Assessments

This year scientists looked at several key indicators to inform resource management decisions for fish stocks in the Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea, and Aleutian Islands. These include indicators of water temperature, prey availability, and fish condition.

Ecosystem information was formally considered in 36 fish stock assessments. The acceptable biological catch was reduced due to a combination of factors for two fish stocks. Eastern Bering Sea pollock was reduced noting ecosystem and fisheries performance concerns; the state-wide sablefish catch was reduced due to ecosystem and population dynamics (how a population of a species changes over time) concerns.

The acceptable biological catch estimate represents the overall limit that can safely be removed from the ecosystem without impacting a fish and crab stock’s long-term sustainability. Total allowable catches for individual fisheries that operate in Alaska are set at or below this overall limit for each commercial fish and crab stock.

“It’s important to note that changing ecological conditions and reductions in acceptable biological catch levels don’t necessarily mean lower fishing levels,” said Ivonne Ortiz, editor of the Aleutian Islands Ecosystem Status Report, NOAA affiliate scientist, University of Washington. “In some cases existing management measures are sufficient to address uncertainty associated with changes in environmental conditions.”

Continuing to monitor environmental conditions and climate change effects on Alaska marine ecosystems is really important.

“In the past few years we have witnessed some of the most dramatic environmental changes over the 40-year history of our research surveys,” said Robert Foy, Science and Research Director for the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “The more we can learn about the linkages between changing environmental conditions, and fish, and ecosystem productivity, the more successful we will be at maintaining sustainable commercial, recreational, and subsistence fisheries and healthy coastal communities in Alaska over the long term.”