A microscopic marine alga is thriving in the North Atlantic to an extent that defies scientific predictions, suggesting swift environmental change as a result of increased carbon dioxide in the ocean, a study led a by Johns Hopkins University scientist has found.

What these findings mean remains to be seen, as does whether the rapid growth in the tiny plankton’s population is good or bad news for the planet.

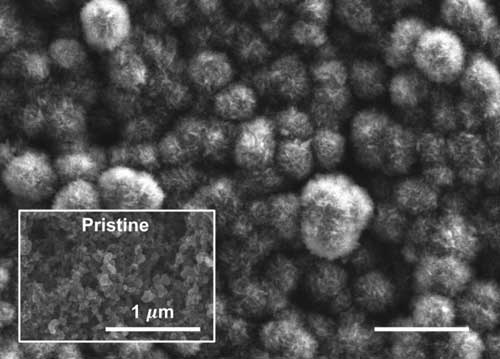

Published today in the journal Science, the study details a tenfold increase in the abundance of single-cell coccolithophores between 1965 and 2010, and a particularly sharp spike since the late 1990s in the population of these pale-shelled floating phytoplankton.

“Something strange is happening here, and it’s happening much more quickly than we thought it should,” saidAnand Gnanadesikan, associate professor in the Morton K. Blaustein Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Johns Hopkins and one of the study’s five authors.

Gnanadesikan said the Science report certainly is good news for creatures that eat coccolithophores, but it’s not clear what those are. “What is worrisome,” he said, “is that our result points out how little we know about how complex ecosystems function.” The result highlights the possibility of rapid ecosystem change, suggesting that prevalent models of how these systems respond to climate change may be too conservative, he said.

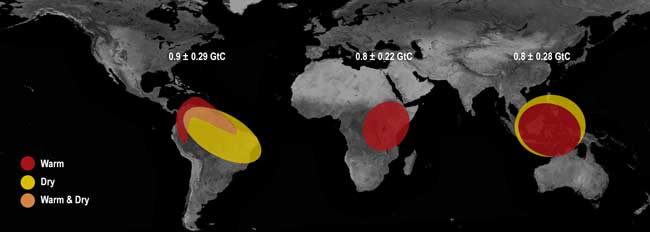

The team’s analysis of Continuous Plankton Recorder survey data from the North Atlantic Ocean and North Sea since the mid-1960s suggests rising carbon dioxide in the ocean is causing the coccolithophore population spike, said Sara Rivero-Calle, a Johns Hopkins doctoral student and lead author of the study. A stack of laboratory studies supports the hypothesis, she said. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas already fingered by scientific consensus as one of the triggers of global warming.[xyz-ihs snippet=”adsense-body-ad”]

“Our statistical analyses on field data from the CPR point to carbon dioxide as the best predictor of the increase” in coccolithophores, Rivero-Calle said. “The consequences of releasing tons of CO2 over the years are already here and this is just the tip of the iceberg.”

The CPR survey is a continuing study of plankton, floating organisms that form a vital part of the marine food chain. The project was launched by a British marine biologist in the North Atlantic and North Sea in the early 1930s. It is conducted by commercial ships trailing mechanical plankton-gathering contraptions through the water as they sail their regular routes.

William M. Balch of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Maine, a co-author of the study, said scientists might have expected that ocean acidity due to higher carbon dioxide would suppress these chalk-shelled organisms. It didn’t. On the other hand, their increasing abundance is consistent with a history as a marker of environmental change.

“Coccolithophores have been typically more abundant during Earth’s warm interglacial and high CO2 periods,” said Balch, an authority on the algae. “The results presented here are consistent with this and may portend, like the ‘canary in the coal mine,’ where we are headed climatologically.”

Coccolithophores are single-cell algae that cloak themselves in a distinctive cluster of pale disks made of calcium carbonate, or chalk. They play a role in cycling calcium carbonate, a factor in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. In the short term they make it more difficult to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but in the long term—tens and hundreds of thousands of years—they help remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and oceans and confine it in the deep ocean.

In vast numbers and over eons, coccolithophores have left their mark on the planet, helping to show significant environmental shifts. The White Cliffs of Dover are white because of massive deposits of coccolithophores. But closer examination shows the white deposits interrupted by slender, dark bands of flint, a product of organisms that have glassy shells made of silicon, Gnanadesikan said.

“These clearly represent major shifts in ecosystem type,” Gnanadesikan said. “But unless we understand what drives coccolithophore abundance, we can’t understand what is driving such shifts. Is it carbon dioxide?”

The study was supported by the Sir Alister Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science, which now runs the CPR, and by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. Other co-authors are Carlos del Castillo, a former biological oceanographer at APL who now leads NASA’s Ocean Ecology Laboratory, and Seth Guikema, a former Johns Hopkins faculty member now at the University of Michigan.

Source: Johns Hopkins [xyz-ihs snippet=”Adversal-468×60″]