Gui ciqlluami et’aarllianga. – I used to live in a sod house.

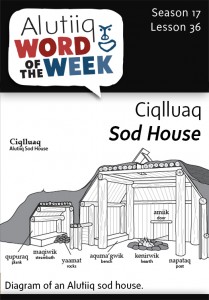

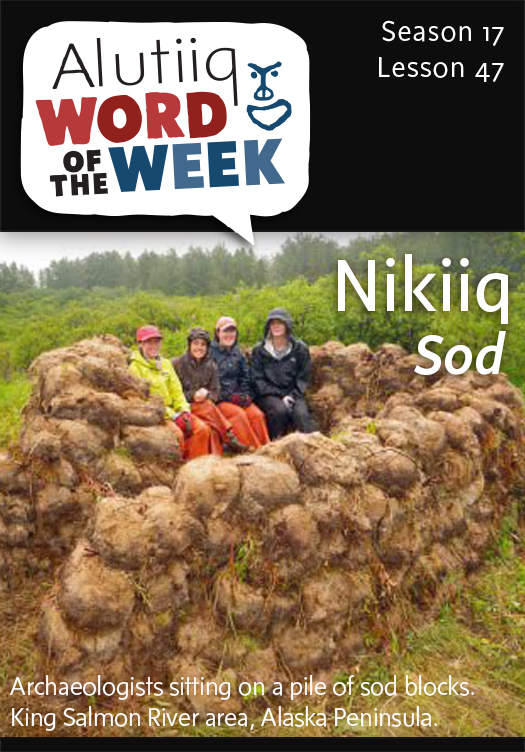

Known today by the Russian word barabara, the tradition Alutiiq house was a sod and thatch-covered structure built partially underground (semi-subterranean). After digging a foundation pit, builders erected a post-and-beam framework and covered it with planks split from driftwood. Over the wooden frame, they piled sod for insulation.

Houses were entered through a low door that led into a large room with a central hearth. Around the walls were earthen benches for sitting and sleeping. Dry grass or animal skin, particularly bear hides, covered these benches. This is where Alutiiq people cooked, repaired tools, sewed clothing, and hosted visitors.

Attached to the central room were a series of side chambers. Accessible through narrow passageways, people used these rooms for sleeping, steam bathing, and food storage. Groups of related Alutiiq women and their families lived together. Each family had its own sleeping room but shared the large central room.

In addition to houses, Alutiiqs built sod-covered structures for community activities. These large, single-roomed buildings also had benches along the walls. Here, men gathered to socialize, plan war parties, discuss political issues, and lead community festivals. Women and children joined these festivals but as a rule did not visit these community houses regularly. Russian observers noted that most communities had one such structure, although it is not clear whether these “men’s houses,” as they are sometimes called, were owned by wealthy community leaders or simply maintained by the wealthy. Whatever their ownership, the use of community houses is a practice Alutiiqs share with their Yup’ik and Iñupiat neighbors.

Historic photographs show Alutiiq families living in sod houses about one hundred years ago. As the American fishing industry introduced large quantities of western goods, wood-framed structures gradually replaced sod houses. Alutiiq Elders remember that as frame houses replaced traditional sod houses in the early twentieth century, the old, sod-covered buildings became gathering places for steam bathing, processing foods, and playing games. Today, sod houses are used for social and ceremonial gatherings as a proud symbol of Native heritage.