Scientists find that some Pacific cod may be more vulnerable to climate change than others.

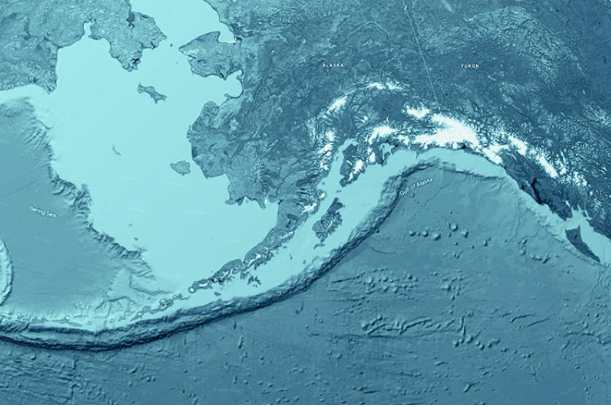

Much of the success in managing U.S. fish species has come with recognizing local differences and genetic variability within species. Pacific cod are an important commercial fish species caught throughout Alaskan waters. Cod caught in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea are managed as separate stocks. A new genetics study found that the relationship between the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska may be a bit more complicated than originally thought.

A genetic break between the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska may fall further to the east than is currently designated under existing management measures. Scientists also found genetic evidence to suggest that localized environmental conditions may be critical to Pacific cod development and survival.

The Evolution of the Pacific Cod

Pacific cod is believed to have originated from an Atlantic cod ancestor that moved into the Pacific Ocean 4 million years ago. Today, Pacific cod are found throughout the Western Pacific. They are found in the Eastern Pacific along the Korean Peninsula. In the United States, their range extends from the Chukchi Sea to as far south as northern California. Populations at the southern edges of both the eastern and western Pacific show distinct genetic differences from northern populations.

Pacific cod undertake annual feeding migrations that are not well understood. However, scientists know that Pacific cod typically return to their natal spawning areas during winter months to reproduce.

“While many of the genetic differences between Pacific cod populations can be explained by reproductive isolation caused by strong homing behavior, the mechanisms underlying these differences have not been specifically explored,” said Ingrid Spies, stock assessment scientist and geneticist with the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “Such selective processes are increasingly relevant to the effective management of Pacific cod, given recent ocean warming events that have resulted in steep declines in Gulf of Alaska populations and anomalous summer feeding migrations into the northern Bering Sea.”

NOAA Fisheries scientists have found that these events emphasize sensitivity to temperature related to growth and survival in Pacific cod. There is a broad species range of Pacific cod, from the temperate climates of Korea and the Pacific Northwest to the arctic and subarctic conditions of the Bering and Chukchi Seas. This also suggests that local populations of cod are adapted to thermal profiles specific to their habitat.

In this study, Spies and her colleagues looked at a specific gene region called zona pellucida or ZP3. They wanted to assess its role in geographic variation among Alaska’s two Pacific cod stocks.

Scientists have studied ZP3 in other mammals and fish. In other species, it plays a key role in reproductive isolation. This is when related species are not able to successfully breed. This is possibly due to the fact that they reproduce at different times of the year or have other behavioral or physiological differences.

ZP3 also helps prevent polyspermy, in which two sperm fertilize a single egg. When this happens the embryo may die. ZP3 protects the embryo and aids in the fertilization process. In Antarctic fish eggs, ZP3 also produces an antifreeze protein that helps fish survive in colder water.

The Role of ZP3 in Defining Alaska Pacific Cod Stocks

Scientists examined the genetic structure of 230 samples collected from 16 spawning locations during the winter spawning season December-May (2003–2019). The samples were collected during this time when fish were spawning to avoid the chance of stock mixing.

They found that the genetic structure of fish, at the ZP3 gene, from the Aleutian Islands, Bering Sea, Shumagin Islands, and Kodiak collections were similar and distinct from fish found in Prince William Sound and southward. This suggests that selective pressures such as water temperature may be affecting Pacific cod development at small spatial scales within the Gulf of Alaska.

According to Spies, further work is needed to study the role of ZP3 in Pacific cod found throughout the Gulf of Alaska. It could play a role in whether some populations of fish are more or less tolerant to warming ocean temperatures. In other work by NOAA Fisheries stock assessment scientists have found evidence that cod at early life stages are particularly vulnerable to temperature shifts. Warm temperatures also affect prey availability for both young and adult fish in the Gulf of Alaska.

Spies suspects that this may be the case as during and after the heatwave in the Gulf of Alaska (2014–2016). During that period, the population size of the Eastern Gulf of Alaska cod stock remained low but stable. In contrast, the cod stock in the Central Gulf of Alaska declined by about 30 percent per year, and by 23 percent per year in the Western Gulf of Alaska.

“We also need wider-scale sampling of fish caught in winter and summer fisheries from the Shumagin Islands and Kodiak to have a more complete picture of genetic diversity across seasons. Currently these areas are managed as part of the Gulf of Alaska stock, but results from this work suggest that fish found here, at least during the winter, are more of a match for fish found in the Bering Sea.”