From left, Coda Consulting CEO Mathieu Gibeault, Eyal Saiet of ACUASI, and Gislain Chevrette, also of Coda, stand atop the new icing tower at the University of Alaska Fairbanks on Feb. 5, 2025.

A new icing tower at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute will help aerospace engineers figure out how to enable drones to fly safely in icy weather.

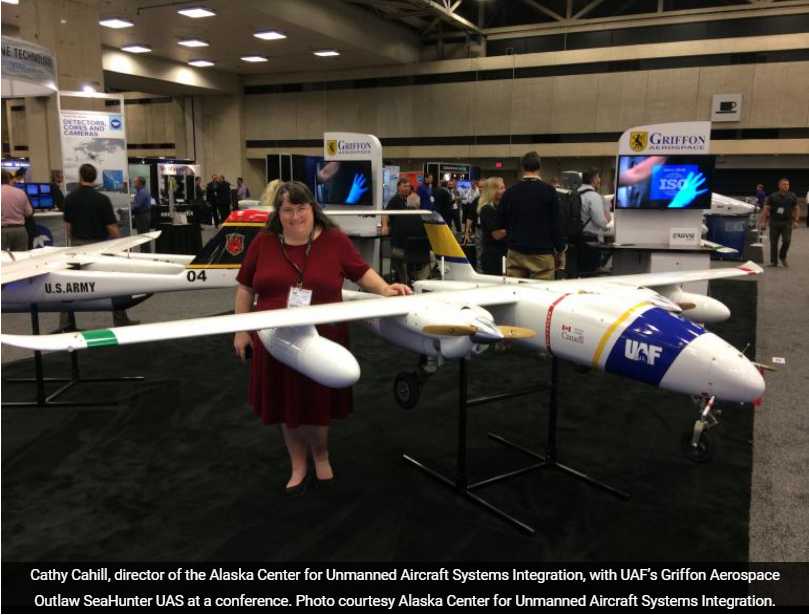

That’s important as Alaska accelerates an effort to use drones for deliveries to remote communities and for emergency response in harsh weather conditions. The Alaska Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Integration at the UAF Geophysical Institute is leading the work.

Ice build-up on wings or rotor surfaces alters airflow, degrading lift and affecting aircraft control. That’s a potentially catastrophic problem for drones and crewed aircraft traveling in clouds or ascending through them to cloud-free altitudes where icing doesn’t occur.

Drones operate at such low altitudes that they are regularly susceptible to icing.

“If drones are going to be a robust option for cargo delivery, for search and rescue and for other uses, then they need to be reliable,” said Eyal Saiet, systems and technology integration specialist at ACUASI. “They have to be able to handle icing, and in Alaska that’s a major barrier to cross.”

Aircraft icing can occur at altitudes ranging from near the surface up to 40,000 feet, depending on conditions such as temperature, moisture and cloud type. The severest icing typically occurs between 2,000 and 20,000 feet, where supercooled liquid water droplets are most prevalent.

“An airplane flying 20,000 feet at 800 miles an hour or so has very little risk of icing as opposed to a drone flying very low and close to the ground,” Saiet said.

Federal Aviation Administration regulations categorize icing into large and small droplets.

Large drops present more of a challenge, as they interact differently on impact with cold surfaces than smaller drops do. Larger drops tend to shatter when hitting the aircraft, then reattach and freeze to surfaces outside of the ice protection area.

ACUASI’s ice tower is somewhat like a wind tunnel commonly used to test aircraft, except it’s smaller and vertical. The ACUASI tower is about 16 feet tall and located in a fenced area behind UAF’s Reichardt Building.

The tower can create various types of calibrated icing conditions, enabling drones to fly in a controlled environment that simulates real-world scenarios.

Coda Consulting of Ottawa, Canada, designed and built the tower, enhancing an experimental setup developed by David Orchard of the National Research Council of Canada.

The new ACUASI icing tower can reproduce a wide range of icing scenarios, making it a critical asset for advancing drone safety and performance in harsh weather conditions.

“Our collaboration with NRC on spray nozzle calibration was key in ensuring that we could precisely control droplet size and liquid water content, allowing us to create accurate supercooled water droplet icing conditions for testing,” said Gislain Chevrette, an icing expert with Coda.

Coda Consulting CEO Mathieu Gibeault called the new tower a “truly one-of-a-kind facility.”

“We saw an opportunity to take an innovative test facility design and enhance it by leveraging our years of expertise in icing test systems and automation,” he said.

[content id=”79272″]