Venus was once Earth-like and maybe even habitable. Why is it so different from Earth now?

This week NASA announced its selection of four finalists in its Discovery Program competition, and one of the selected groups hopes to help find an answer.

UAF Geophysical Institute research professor Robert Herrick is a member of the science team for one of the proposals, the VERITAS mission, which would map Venus’ surface to determine the planet’s geologic history.

NASA’s Discovery Program invites researchers to design planetary science missions that deepen what we know about the solar system and our place in it. Each of the four teams will receive $3 million to develop their proposals within nine months. Final mission selections will be made next year.

“These selected missions have the potential to transform our understanding of some of the solar system’s most active and complex worlds,” Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said in a press release. “Exploring any one of these celestial bodies will help unlock the secrets of how it, and others like it, came to be in the cosmos.”

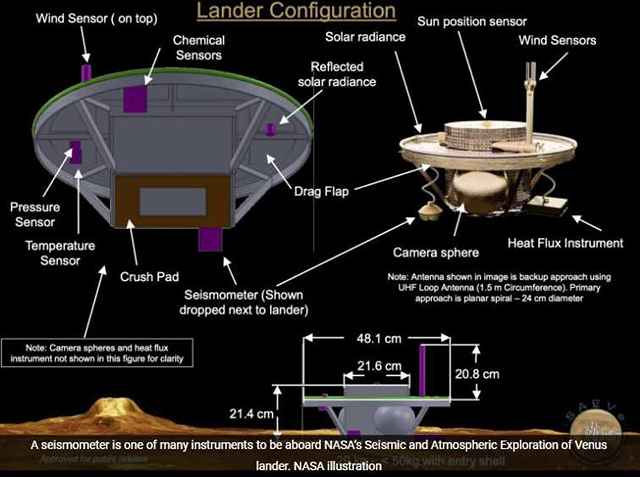

VERITAS — the Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy mission — proposes using radar to obtain images and topography information about the surface of Venus at much higher resolution than previous missions. It would also use a specially designed camera that could collect compositional information about the planet’s geology, which is largely unknown. Suzanne Smrekar of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, is the principal investigator.

[content id=”79272″]

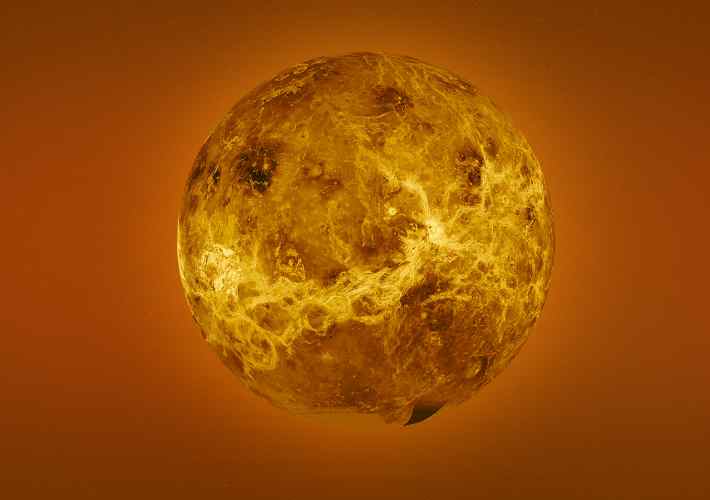

Venus is both remarkably similar to and strikingly different from Earth. It is 10 percent smaller than Earth, and its distance is only 30 percent closer to the sun. To planetary scientists, these differences are quite small.

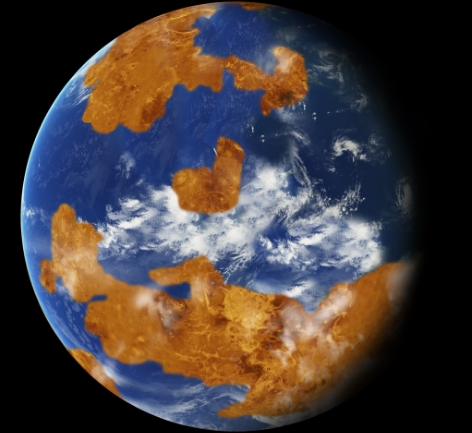

Recent discoveries suggest that Venus may have granitic rocks similar to those that form much of the Earth’s continents. To produce granite on Earth requires, among other things, water moving from the surface into the subsurface as part of plate tectonics.

“If there’s a lot of this type of rock on Venus, it is an indicator that at some point in Venus’ past, it was a lot more Earth-like and was probably habitable,” Herrick said. It might have been able to sustain life during its first 2 billion to 3 billion years.

Venus today is completely uninhabitable. For one thing, the surface of the planet is about 900 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Then this whole issue of other planets and other solar systems gets even more complicated,” Herrick said. “You have the possibility of something being able to support life, but only for a window of time, and then that possibility goes away.”

Herrick believes Venus’ history can help us understand what creates a habitable planet and what could cause extreme changes.

The mission proposes to orbit Venus with a synthetic aperture radar to create three-dimensional reconstructions of topography and confirm whether processes such as plate tectonics and volcanism are active.

VERITAS would be the first NASA spacecraft dedicated to a Venus visit since the 1989 Magellan mission, in which Herrick participated as a graduate student. An expert in remote sensing and planetary science, Herrick hopes to take his experience analyzing Magellan data and apply it to the new mission.

Herrick plans to compare geophysical information, such as the planet’s gravity field, with surface features, including craters created by the impact of meteorites, to evaluate the history of Venus’ landscapes.

On Venus, impact craters are produced at a relatively well-understood rate, so they provide a rough calendar. If nothing happens to an area, more craters accumulate. However, if something like volcanic flows occur in a region, they will fill craters with lava.

This process can be used to understand the relative age of events. For example, the dark areas of the moon have fewer craters because volcanism covered most of them about a billion years into the moon’s history.

If selected as an official mission, VERITAS would launch in May 2026, enter Venus orbit by the end of the year and start collecting data immediately.

After a career of studying Venus, Herrick would be excited to see the mission come to fruition.

“You get to make these major science discoveries,” he said. “You get to be in the [control] room and you get to see brand new pictures of a planet, [pictures] that we haven’t seen before.”

“It’s the same motivation of explorers over the years. We want to see, I want to see, something nobody else has seen before.”

Source: UAF