Permafrost expert Tom Douglas in a recent ground-collapse feature, in which he found a young, dead moose.

High summer is here in middle Alaska. North of Fairbanks, in bright sunshine, alder flycatchers are perched in spruce tops, just arriving from Bolivia and Peru. A few steps away, accompanied by the smell of sulfur, dozens of carrion flies buzz on and above a moose carcass.

Permafrost expert Tom Douglas has led me here, to a hilltop just above the world-famous Permafrost Tunnel in Fox. The landscape on top of the tunnel looks like typical boreal forest in Alaska, covered with spruce and moss and Labrador tea. It also features a sinkhole, known by scientists as a thermokarst, which holds the shrinking remains of a young moose. It probably died this spring.

“Imagine this place in late winter, with deep snow and all these punji sticks,” Douglas said while climbing down into the hole. “You have to wonder, did the moose get stuck in here?”

Douglas works for the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory at nearby Fort Wainwright. He found the dead moose while walking around on this bench above the Permafrost Tunnel — an H-shaped underground study portal of frozen silt and clear ice wedges as large as motorhomes.

Douglas wonders if this young moose somehow got trapped in this depression and was not able to climb out. Maybe it broke a leg?

While standing over the festering moose, Douglas points out meat on the animal’s ribs, along with internal organs undamaged, seeming proof that a hungry bear or wolf did not pull it down. There are no large animal tracks nearby in the mud.

Did this northern sinkhole kill the moose? Thawing permafrost — ground that has remained frozen through the heat of at least two summers — is usually a slow-motion disaster, resulting in slowly sinking buildings and roller-coaster roads.

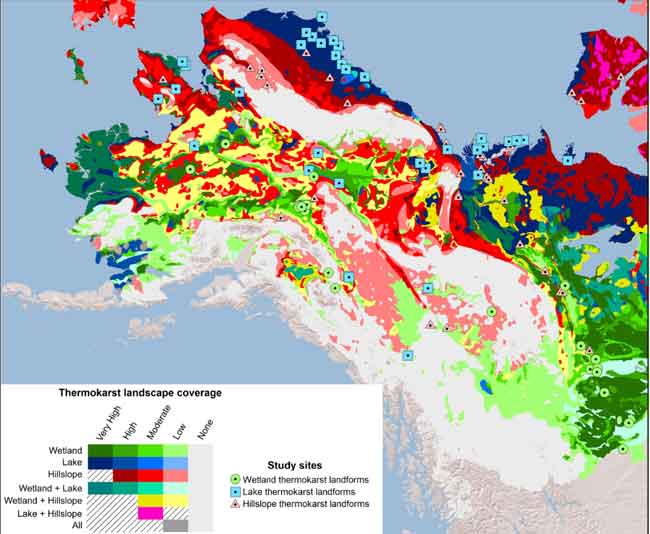

Douglas — along with many other scientists and nonscientists — is noticing more thermokarst features opening up in Alaska. And the holes are happening fast, some appearing in just a few days, or over a single summer.

[content id=”79272″]

Warmer air temperatures all over the world, and especially in the north, have accelerated the thawing of frozen soil. Permafrost, which lies beneath one quarter of all the land north of the equator, is a relic of colder times on Earth, when frigid temperatures penetrated deep.

“Did you notice that Fairbanks’s average temperature for 2019 was above zero degrees C?” Douglas said, noting that hasn’t happened often in maybe hundreds of thousands of years. Fairbanks’ average temperature was also slightly above freezing one other year, in 1926, according to records meteorologists have kept since 1906.

“It’s tough to keep permafrost frozen when it’s above freezing,” he said.

Because water is warmer than ice and percolates down, it thaws permafrost. Douglas recently co-authored a paper on rainy years for Fairbanks in 2014 and 2016, and the extensive permafrost disappearance that followed.

Permafrost specialist Tom Douglas pauses on the ice of a Fairbanks creek that shows recent bank erosion, probably due to the thawing of soil that had been frozen for many years.

“It’s pretty dramatic what water can do,” Douglas said. “In many places, the typical summer thaw has doubled or tripled what it has been in the past.”

Temperature sensors he recently installed at a site nearby showed that frozen soil six feet down has transformed to unfrozen soil. By chance, Douglas had placed the station at a spot just before it underwent a change for the first time in perhaps thousands of years.

“I’ve been studying this for 18 years, and this is a pretty exciting time,” he said.

He will return this summer and bore a deeper hole there to see if he can again reach the permafrost, but he might need a drill rig instead of hand tools.

Last year’s cold winter (Fairbanks’s high temperature for January, 2020, was 4 degrees F) might have recharged Interior permafrost, Douglas said, but scientists won’t know until later in the summer. The trend is headed toward less permafrost, a problem that is becoming more visible — and, maybe for unlucky moose, fatal.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell ned.rozell@alaska.edu is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.