“This green line looks like the death of permafrost — it’s flatlining,” Louise Farquharson said to an audience of a few dozen scientists.

Her quiet voice came through speakers over the muffled clicking of keyboards and occasional coughs in a dimly lit room at the 2019 American Geophysical Union fall meeting in San Francisco.

She was showing a graph describing her newest research findings on one of the most important, and ignored, parts of the frozen Earth.

Her reserved tone hid a bombshell message — by 2035 permafrost thaw may continue on its own, disregarding the processes that have kept it frozen for thousands of years.

Farquharson is a research associate at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute. She is an expert on permafrost, the parts of the ground that stay frozen for at least two consecutive years.

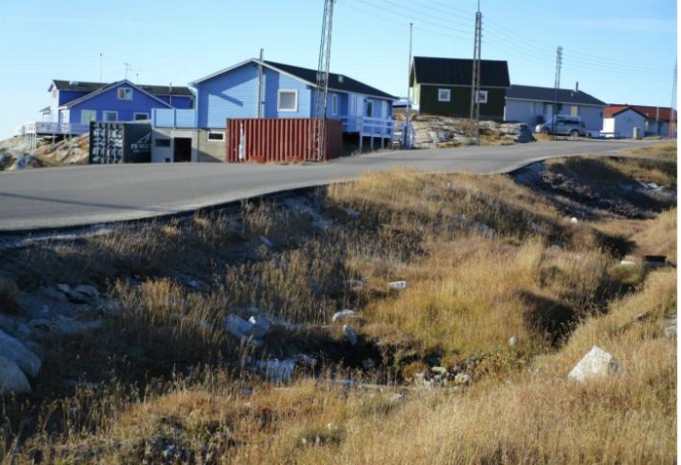

Permafrost zones occupy about 24 percent of the exposed land surface of the Northern Hemisphere. However, the permafrost is shrinking. The Arctic is, and will, experience the most dramatic effects of global warming, so it’s no surprise that permafrost is thawing, to the detriment of the sub-Arctic, Arctic and the planet.

Permafrost thaw causes the ground surface to sink, which leads to infrastructure damage, accelerates microbial activity and releases carbon and other gases into the atmosphere, accelerating global warming even more. Most experts suggest permafrost thaw will continue and even speed up as we go into the next century.

However, calculated rates of thaw may be far lower than what will really happen. According to Farquharson, a key accelerating factor in permafrost thaw has been dramatically underestimated.

“It’s the Arctic’s ‘grand reveal,’” Farquarson said. “We thought we saw what was happening, then it really stepped out from behind the curtain.”

This factor is called talik, thawed zones in permafrost areas.

The mixture of wet, frigid dirt is commonly associated with Arctic thermokarst lakes that form when enough ice-rich permafrost thaws to create a body of water.

The talik beneath these lakes significantly contributes to the thawing process. Just as icewater melts faster than a lone cube of ice, the waterlogged ground accelerates thawing of the permafrost around it.

Normally talik has been thought of as limited to the areas just below and around thermokarst lakes, but Farquharson’s work shows they are much more extensive.

Farquharson and her collaborators, including Vladimir Romanovsky, also at the Geophysical Institute, observed substantial evidence from 28 sites across Alaska showing these taliks are larger, and extend deeper in the ground, than previously thought — even in many areas scientists didn’t know it existed.

[content id=”79272″]

This could have dramatic effects on permafrost, making previous thaw forecasts and estimates of subsequent carbon release pale in comparison to what is coming.

“You look at your lake distribution of taliks and how much of the landscape that accounts for, and then you take that number and you spread it across pretty much the entire landscape in Interior Alaska,” she said.

“We’re going to basically change the calculations for global carbon emissions.”

To maintain permafrost, the ground has to be exposed to frigid air for a period of time before snow falls. During warmer years or years when snow falls earlier, the snow insulates the ground while it’s still warm, like a down comforter trapping heat in the ground. This promotes thaw.

For the past two to three years, Farquharson has seen more thaw than freeze, which means more talik. However, this is still tied to snowfall. If enough talik develops, even snowfall won’t halt thaw.

“It’s going to be a really important mechanism for speeding up thaw,” she said. “It’s going to be a really important mechanism of carbon release that I think is going to dwarf what we have been [expecting].”

Source: Geophysical Institute