The American blue economy, which are resources and services provided by the oceans, contributed about $373 billion to the economy in 2018, and fisheries play a large role in that. Climate change, however, threatens commercial and recreational fisheries; changes in water temperature can affect the environments where fish, shellfish, and other marine species live, and cause them to seek new waters. A new indicator, jointly developed by the EPA and NOAA, shows that along the coasts, marine species are shifting northward or to deeper waters, and as smaller prey species relocate, predator species may follow.

The American blue economy, which are resources and services provided by the oceans, contributed about $373 billion to the economy in 2018, and fisheries play a large role in that. Climate change, however, threatens commercial and recreational fisheries; changes in water temperature can affect the environments where fish, shellfish, and other marine species live, and cause them to seek new waters. A new indicator, jointly developed by the EPA and NOAA, shows that along the coasts, marine species are shifting northward or to deeper waters, and as smaller prey species relocate, predator species may follow.

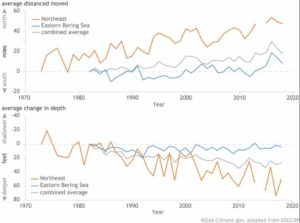

The U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), which facilitates coordination of Earth science research across 13 federal member agencies, has published this marine species distribution indicator using NOAA data. The graphs show the annual change in latitude and depth of 140 marine species along the northeastern U.S. coast and in the eastern Bering Sea. Changes in geographic distribution have been aggregated across all 140 species. In waters off the Northeast, fish and shellfish are moving northward at a significant rate; in the eastern Bering Sea, they are still shifting northward but at a lesser rate. Likewise, marine species in both regions are moving to deeper waters, but the rate of change in depth is especially high along the northeastern coast.

[content id=”79272″]

The maps show the annual geographic distribution for three species (Alaska pollock, snow crab, and Pacific halibut) in the eastern Bering Sea from 1982 to 2018 (left) and for three species (American lobster, red hake, and black sea bass) along the northeastern U.S. coast from 1973 to 2018 (right). The species in waters off the Northeast have shifted northward by an average of 110 miles since the early 1970s, while the species in Alaskan waters have generally shifted away from the coast since the early 1980s and moved northward by an average of 19 miles.

Researchers chose these mapped species because they represent abundant fish and shellfish from a variety of habitats. Additionally, due to these species’ abundance, overfishing will not impact the data tracked in the indicator. Indicators are critical to USGCRP’s capacity to monitor and observe climate change and its impacts. This new indicator should strengthen our ability to detect warming oceans, as marine species respond strongly to changes in water temperatures and large, multivariable data sets exist for many fish and shellfish.

Source: NOAA