Scientific instruments hang over the ice-free Arctic Ocean during one of the expeditions that contributed data to a recent study published in Frontiers of Marine Science. Sea ice can be seen on the horizon.

New research explores how lower-latitude oceans drive complex changes in the Arctic Ocean, pushing the region into a new reality distinct from the 20th-century norm.

The University of Alaska Fairbanks and Finnish Meteorological Institute led the international effort, which included researchers from six countries. The first of several related papers was published this month in Frontiers in Marine Science.

Climate change is most pronounced in the Arctic. The Arctic Ocean, which covers less than 3% of the Earth’s surface, appears to be quite sensitive to abnormal conditions in lower-latitude oceans.

“With this in mind, the goal of our research was to illustrate the part of Arctic climate change driven by anomalous [different from the norm] influxes of oceanic water from the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, a process which we refer to as borealization,” said lead author Igor Polyakov, an oceanographer at UAF’s International Arctic Research Center and FMI.

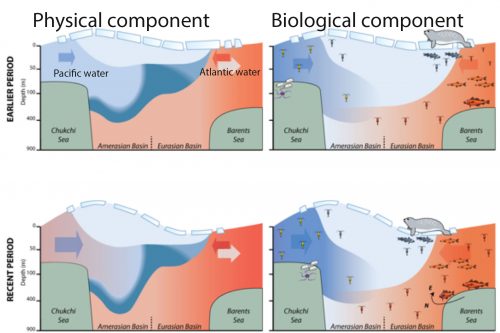

Although the Arctic is often viewed as a single system that is impacted by climate change uniformly, the research stressed that the Arctic’s Amerasian Basin (influenced by Pacific waters) and its Eurasian Basin (influenced by Atlantic waters) tend to differ in their responses to climate change.

Since the first temperature and salinity measurements taken in the late 1800s, scientists have known that cold and relatively fresh water, which is lighter than salty water, floats at the surface of the Arctic Ocean. This fresh layer blocks the warmth of the deeper water from melting sea ice.

A map of the Arctic Ocean shows the location of the Amerasian and Eurasian basins. Arrows show the path of warm, fresh Pacific water and warm, salty Atlantic water into the region.

In the Eurasian Basin, that is changing. Abnormal influx of warm, salty Atlantic water destabilizes the water column, making it more susceptible to mixing. The cool, fresh protective upper ocean layer is weakening and the ice is becoming vulnerable to heat from deeper in the ocean. As mixing and sea ice decay continues, the process accelerates. The ocean becomes more biologically productive as deeper, nutrient-rich water reaches the surface.

[content id=”79272″]

By contrast, increased influx of warm, relatively fresh Pacific water and local processes like sea ice melt and accumulation of river water make the separation between the surface and deep layers more pronounced on the Amerasian side of the Arctic. As the pool of fresh water grows, it limits mixing and the movement of nutrients to the surface, potentially making the region less biologically productive.

The study also explores how these physical changes impact other components of the Arctic system, including chemical composition and biological communities.

Retreating sea ice allows more light to penetrate into the ocean. Changes in circulation patterns and water column structure control availability of nutrients. In some regions, organisms at the base of the food web are becoming more productive. Many marine organisms from sub-Arctic latitudes are moving north, in some cases replacing the local Arctic species.

“In many respects, the Arctic Ocean now looks like a new ocean,” said Polyakov.

These differences change our ability to predict weather, currents and the behavior of sea ice. There are major implications for Arctic residents, fisheries, tourism and navigation.

This conceptual model shows the influx of Pacific and Atlantic water into the Arctic Ocean in the past compared to recent years. Blue indicates cool water and red indicates warm water. Arrows indicate the direction of water flow.

This study focused on rather large-scale changes in the Arctic Ocean, and its findings do not necessarily represent conditions in nearshore waters where people live and hunt.

The study stressed the importance of future scientific monitoring to understand how this new realm affects links between the ocean, ice and atmosphere.

Co-authors of the paper include Matthew Alkire, Bodil Bluhm, Kristina Brown, Eddy Carmack, Melissa Chierici, Seth Danielson, Ingrid Ellingsen, Elizaveta Ershova, Katarina Gårdfeldt, Randi Ingvaldsen, Andrey V. Pnyushkov, Dag Slagstad and Paul Wassmann.

Source: UAF