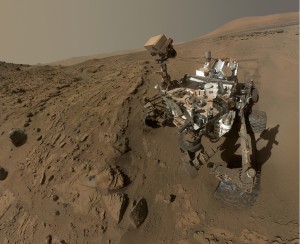

Image courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS.

Following a press conference at the enormous fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco, an unusual sound was heard in a room of reporters: Applause.

Writers and videographers representing news agencies from around the world clapped at the conclusion of a presentation by four scientists involved with the NASA mission to Mars, now in its second year. After a year of cautious data checking, there was big news on this day.

John Grotzinger, head of the Mars Science Laboratory mission, announced that methane the Curiosity rover detected on Mars “can both be consistent with the former or current presence of life.”

Clicking fingers on keyboards filled the conference room as Grotzinger spoke in a sure, soothing tone. Moments later, outgoing tweets pierced the walls of the Moscone Center.

The news, now a week old: the superintelligent Mars rover Curiosity found a whiff of methane in a dirt sample it analyzed within its belly. On Earth, methane wafts from living creatures 95 percent of the time. But, there is also a chance the methane was produced by a non-living thing, a reaction of sunlight on rocks or ancient water-rock interactions. The methane was a lonely spike in samples from more than one year ago, but it was real and the scientists will steer Curiosity for more.

“We may never get lucky again,” Grotzinger said. “We may never find more organics. But maybe we will.”

Seeing those men whose minds have figured out how to perform science on a rolling platform 50 million miles away was a nice reminder — nurtured curiosity gives birth to great science. When a government supports that enthusiasm, cool things happen.

Such as calculating how to sail an instrumented vessel close to Pluto, nine years away using the fastest means we know. The Pluto mission was the subject of another reporter gathering set up by the conference’s media organizers.

Once considered the ninth and most distant planet in our solar system, Pluto is now known as a dwarf planet. It’s as big as half the continental U.S. and is 40 times farther away from the sun. Because of that distance, surface temperatures on Pluto are about 300 degrees below zero. The best image of it we have now is a pixelated gray beach ball.

That will change this summer, said Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute. The head of the New Horizons mission described how a capsule he helped launch in 2006 will intercept Pluto’s orbit in July 2015. It has taken that long for the spacecraft to travel the three billion miles from Earth to Pluto. On its close pass in July, New Horizons will send images back to Earth with a detail equivalent to a satellite that lets you name the lakes in New York’s Central Park.

The researchers compare the Pluto mission, to which they have been committed since before they needed bifocals, as the Everest of planetary exploration.

“This is the final ascent to the summit and I’m thrilled to be along for the ride,” said planetary expert William McKinnon of Washington University in St. Louis.

When a reporter brought up the subject of Pluto not being a real planet, McKinnon reminded him that planetary science is still an elementary textbook, its new discoveries limited only by one’s sense of wonder.

“Every time we get a new telescope, there are more and more things out there,” McKinnon said. “It just never seems to end.”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.