A few hours of a December day may affect living things for years to come in the middle of Alaska.

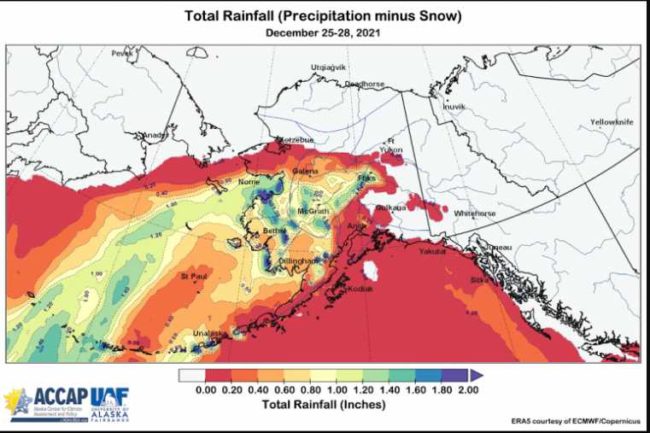

On Dec. 26, more than an inch of rain fell over a wide swath of the state. Much of the backcountry of Interior Alaska now has an ice sheet beneath a foot of fluffy snow.

With half of the seven-month winter yet to come, things look grim for creatures not adapted to rainfall in winter, when supercooled surfaces turn water falling from the sky into a sheet of glass.

All the streets in Fairbanks are now ice roads grooved corduroy by grader blades. Animals without the benefits of heavy equipment are not as lucky.

“The current conditions are as bad or worse as those back in the mid-1960s,” said Dick Bishop, a retired Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologist who has lived in Alaska since 1961. “I don’t remember when we ever had this kind of ice layer.”

Bishop once documented a large moose die-off in the Tanana Flats south of Fairbanks due to deep snows in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Moose are suffering in these conditions because they can’t move far without using a lot of energy, Bishop said. Postholing makes it harder to find food, as well as escape predators.

“Wolves are able to travel on top of this crust,” Bishop said. “That’s a heck of an advantage.”

In area of the Interior where wolves usually don’t venture, like the network of roads and houses near towns and villages, moose have congregated on roads and around houses.

University of Alaska Fairbanks ecologist Knut Kielland recently fended off a cow moose in his driveway, smacking it on the nose with his walking stick.

“Snowshoeing around my house recently the crust was a good 2 inches thick in places,” Kielland said. “I reckon those moose are getting sore shins.”

“But at least their grub is above the crust (moose eat frozen buds and twigs of willow, aspen and birch trees),” he said. “I feel bad for foxes, coyotes, and owls trying to get a meal now. I would think mousing through this crust is a nonstarter.

“I am also curious as to how the winter will unfold for the vole tribe,” Kielland said. “The crust is likely to slow the diffusion rate of carbon dioxide out of the snowpack. If so, everyone beneath the crust will sooner or later be in need of fresh air. How well they can chew their way thru the crust remains to be seen.”

Bishop once estimated that about half of the moose population in the Tanana Flats south of Fairbanks died during the deep-snow winters in 1965-1966 and 1970-1971. Biologists won’t know the fate of Interior moose until the winter ends.

“We don’t expect many of the calves to survive the winter but are hopeful the adults will make it through,” biologist Tony Hollis wrote in a Jan. 5, 2022 press release from the Fairbanks office of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.[content id=”79272″]

How weird was it to have a summer-like rainfall in midwinter this far north?

“There is only one event in Fairbanks history that even approximates this,” said climate researcher Rick Thoman of the International Arctic Research Center. “Over the course of three days, Jan. 18-20, 1937, Fairbanks had 26 inches of snow followed by an inch of rain. (The Dec. 26, 2021) event had less snow but more rain in a bit over half the time, and then was followed by another 8 to 12 inches of snow.”

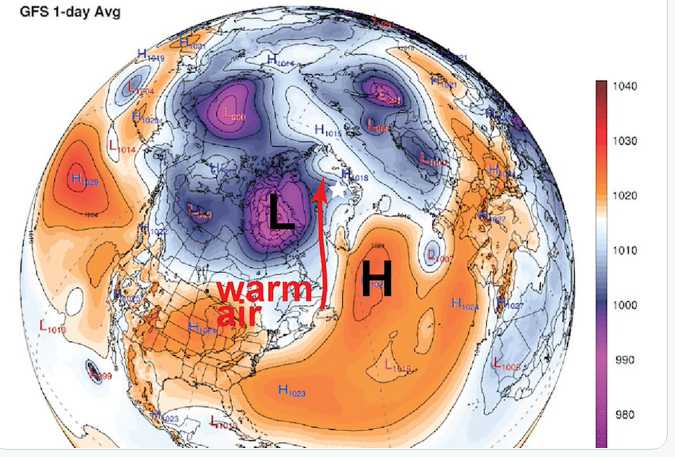

Thoman and forecasters at the Fairbanks office of the National Weather Service saw the rain coming via computer models that days in advance nailed “a Hawaii-to-western-Alaska feed of subtropical moisture” powered by a massive high-pressure system in the North Pacific Ocean. It was the same weather system that was responsible for a temperature of 67 degrees in Kodiak and a record-cold Christmas in Ketchikan.

That wacky pattern mirroring those all over the planet recently is what we might continue to see with a warming world, said Peter Bieniek of UAF’s International Arctic Research Center.

“Rain-on-snow is projected to increase throughout much of Alaska (including Fairbanks) as the climate continues to get warmer and wetter,” said Bieniek, a climate modeler and author of a recent paper on winter-rainfall events in Alaska. “Southern coastal areas may even see a transition from rain-on-snow to rain.”