|

NEW ORLEANS — At this gathering of thousands of scientists at a horseshoe bend in the lower Mississippi River, a few talked about a place far away they have been watching for years.

“The Arctic shows no sign of returning to the reliably frozen state it was a decade ago,” said Jeremy Mathis, an oceanographer with the Pacific Marine Environmental Lab in Seattle.

He was one of four scientists presenting the Arctic Report Card for 2017 at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting. More than 20,000 scientists will walk through the doors of the Morial Convention Center during this second week of December.

Mathis and others, including permafrost expert Vladimir Romanovsky of UAF’s Geophysical Institute, shared many scientists’ 2017 observations of the far North during a press conference.

They reported much of the same news they have since National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientists presented the first Arctic Report Card in 2007: The northern cap of the globe is warming faster than anywhere else on the planet.

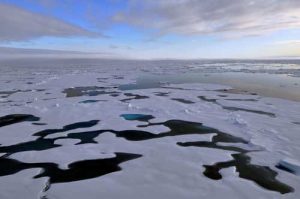

In what Mathis called “the darkening of the Arctic,” less sea ice floating on the northern oceans and fewer days of snow on the ground have allowed blue ocean and brown-and-green tundra to receive more heat from the sun. That seems to be playing out in many ways on the northern stage and beyond.

On March 7, 2017, satellites recorded the lowest amount of winter sea ice floating on the northern oceans since scientists have been able to see the view from 500 miles above starting in 1979.

Chunky, resilient ice that has survived several summers made up only 21 percent of the northern sea ice cover. Most ice is younger and thinner.

Though satellites have allowed overall views of sea ice for only a few decades, a researcher on the panel presented evidence that present low-ice conditions have not existed since at least the Middle Ages.

Emily Osborne of the NOAA Arctic Research Program in Maryland looked at lake sediments, ice cores and plugs of seafloor from the Arctic Ocean to find evidence of ancient debris that floated out on sea ice and then sank, and the remains of tiny creatures called diatoms that live in and around sea ice.

She found that there is no period in the last 1,500 years that shows a similar disappearance of northern sea ice.

“It is normal for sea ice to vary from year to year, but when you move forward into the last couple decades, the magnitude (of sea ice loss) is unprecedented,” she said.

Northern sea ice covered a record low amount of Arctic Ocean a decade ago, in September 2007. When scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center measured the sea ice in November 2017, they found the third-lowest coverage on record. Though 2007 was perhaps not the tipping point that some scientists thought might lead to ice-free Arctic Ocean summers by now, 10 of the lowest sea ice extent years have occurred in the past 11 years.[xyz-ihs snippet=”adsense-body-ad”]Why does less ice matter? Because loss of its mirror-like surface allows the ocean to absorb the sun’s heat.

Some scientists think there is a connection between Romanovsky holding up his phone to show them a well-above average 24 degrees F temperature at his home in Fairbanks and a New Orleans cold snap a few days ago. Snow fell here in this city at 30 degrees north latitude.

“Loss of ice in the Chukchi Sea is reinforcing a very wavy jet stream, which might account for the winds and fires in California and cold in the central and eastern U.S. right now,” said oceanographer Jim Overland of the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

He explained that the current record low sea ice coverage in the Chukchi Sea off the northwest coast of Alaska has provided a lot more heat to the atmosphere.

Conditions in the Arctic have always affected weather at lower latitudes, Overland said after the press conference, but the extra northern heat is helping maintain large-scale patterns that endure longer.

“The jet stream is the door between the Arctic and weather at mid-latitudes,” he said.

That door seems to be open more often now than it has been in the past, he said, allowing warmer Arctic air to flow southward and more often affect weather down here.

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.

Source: Geophysical Institute